Harry Houdini was a master of deception. He mystified crowds with his death-defying routines, appearing to flout the laws of nature. From 1891, Houdini traded on the illusion of immortality – until his death in 1926. Today, in the theatre of financial markets, we remain just as beguiled by the power of illusions. And there is one investors should pay particular attention to – the bezzle.

Economist and historian John Kenneth Galbraith, in 1929’s the Great Crash, described a “period during which an embezzler benefits from stolen money, but the victim does not know he has lost it”. In this time, there is a net increase in psychic wealth. The bezzle is the amount by which they collectively feel better off, between the creation and the destruction of the illusion.

Think of the bezzle another way. Imagine you have a chocolate bar stored in your kitchen cupboard. You scurry home excited, only to find that someone else has snaffled it without telling you. Until that moment, both you and the perpetrator had a warm fuzzy glow of endorphins and anticipation but, for one of you, it was entirely illusory.

And the bezzle is not confined to larceny. The late Charlie Munger, vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, described a functionally equivalent bezzle – or febezzle – the psychic wealth that can be created via legally appropriated money. He defined this as asset values temporarily exceeding their real economic utility. Thus, a divergence occurs between reported (market) and fundamental values. Whereas Houdini’s magic drew gasps of delight, illusions in financial markets can come with ruinous consequences.

What you own versus what you make

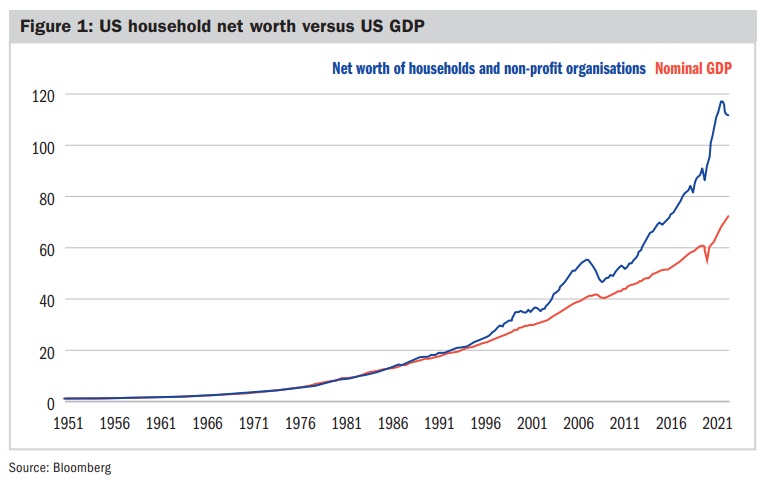

From the 1950s until the early 1990s, the fundamental value of the US economy (measured by GDP) was roughly equal to American households’ net worth. Wall Street accurately reflected the productive value of Main Street.

Since then, asset prices have diverged from their underlying economic utility, sending psychic wealth to record highs. But how can net worth so materially outstrip the productive capacity of the economy? How can you be worth more than you produce?

Forty years of globalisation brought us cheap goods, cheap energy, cheap labour. These forces kept inflation low, pinned interest rates and risk premiums to the floor and ultimately made capital inexpensive. Borrow more, spend more, grow more.

The result was a golden era for asset owners, and the rise of portfolio values created a substantial wealth effect. After all, investors’ behaviour tends to reflect the value of their portfolios.

Psychic wealth, real liabilities

The true cost of the illusion is only exposed when the liabilities of the debt which powered the illusion become due. This is unlikely to happen overnight. Market sell-offs can make a dent in households’ net worth, but the scale of the correction required for asset prices to align with economic value is of a magnitude beyond even the most bearish contemplation.

Policymakers’ attempts to close the gap by stimulating economic growth have been unsuccessful. In fact, fiscal and monetary expansion in response to the pandemic stimulated asset prices considerably more than it did economic output. Magicians never like to reveal the truth behind their tricks.

If the bezzle is to be corrected, we think the mechanism will be more subtle. Asset owners will eventually pay for illusory wealth via financial repression. That is, the rate of inflation will stay above the rate of interest and gradually erode the mounds of capital built up over the past half century.

Tricks today

Magic also occurs at the microeconomic level. One need look no further than the technology sector for further evidence of the bezzle at play. Companies like Uber and Deliveroo were lossmaking for well over a decade, but traded at rich valuations. Investors were willing to pay up for these businesses given the promise of future growth.

But rising interest rates have closed the book on the free money era. Aside from the perceived beneficiaries of artificial intelligence (AI), investors are now far less able or willing to flood companies with capital in order to grow their market share.

These companies can’t afford to keep prices artificially low, and millennials are discovering that their lifestyles are no longer being subsidised by growth-seeking investors. Light regulation can widen the scope of the bezzle, perhaps nowhere more so than in crypto land. The November 2022 implosion of FTX – one of the highest-profile crypto exchanges – made billions of dollars of psychic wealth vanish in a puff of smoke. Will all cryptocurrency wealth prove illusory? On that, the jury is out.

As public markets crashed in 2022, valuations in private markets held firm. But is there more to this stability than meets the eye? Private assets are currently valued at a record premium to their public counterparts, but are they immune to recessionary fears or the effects of tight monetary conditions? Unlikely – they exist, after all, in the same economic reality.

Rather, private equity houses have yet to mark down the values of their assets to reflect the prices others are willing to pay. So are their fees, collected in cold hard cash, based on an imaginary valuation?

Revelation

Perhaps it’s all part of the same trick. The bezzle isn’t necessarily a fraud or Ponzi scheme. It simply describes the accumulation of wealth which – when economic reality catches up – proves illusory. A bezzle becomes insidious or dangerous when imagined wealth is used as collateral for real world liabilities.

As John Stuart Mill put it: “Panics do not destroy capital; they merely reveal the extent to which it has been previously destroyed by its betrayal into hopelessly unproductive works.”

Sadly, when the macroeconomic bezzle is revealed, we will all have to absorb its cost, through a combination of higher taxes, inflation and financial repression. Unlike for Houdini, there may be no miraculous escape.

Ajay Johal is an investment manager at Ruffer

Charity Finance wishes to thank Ruffer for its support with this article