Hardly a day goes by without some new geopolitical twist or turn of events, whether it is conflicting Brexit rhetoric, resolving the dispute in North Korea or simply an awry tweet from President Trump’s account.

Tariffs imposed on the import of steel have remained the focus for investors, with Trump’s rationale centred on the repatriation of jobs in the sector. Unfortunately, when similar measures were imposed by George W Bush in the early 2000s, quite the opposite happened.

The rising cost of steel saw 200,000 jobs cut in industries where steel was an input. This unemployment was greater than the 180,000 jobs in the US steel industry at the time. Tensions continue to build with China and the fractious G7 meeting in early June did little to remedy the US’s trade disputes with its traditional allies.

On the face of it, equity markets continued unfazed. The bond markets, however, are a bit more telling, with bond yields moving up and down much more frequently in the last couple of months. With the added uncertainty of the future of Italian politics and the euro, European bond yields saw volatility not seen since the peak of the Eurozone crisis in 2011.

This was somewhat short lived, but similarly to the surge in volatility in equity markets in February, we believe that this episode provides a window into some of the underlying instability in financial markets. This continues to be masked by supportive policy from the central banks.

We still believe that the backdrop of a reduction in monetary stimulus is becoming increasingly important to the short term outlook for financial markets.

Interest rates

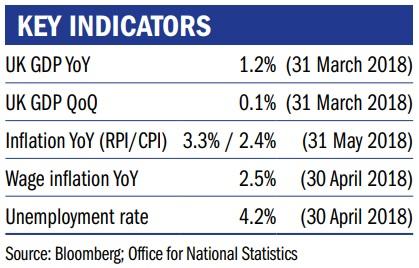

In the US this month, the Federal Reserve has responded to the bullish outlook for the US economy, by raising interest rates a quarter of a per cent to 2 per cent. This was accompanied by a signal that a total of four interest rate rises are now likely in 2018, amidst accelerating growth and a very healthy job market.

They also reiterated their goal to reduce their balance sheet, a programme which will be in full swing by mid-September. Although the Federal Reserve are very much leading the charge on this unwinding, many expect the European

Central Bank to make a pronouncement with regards to their intentions to reduce their own balance sheet as soon as July. It will take some time for financial markets to recalibrate to a regime where the central banks aren’t buying assets and supporting elevated prices.

We think the transition will be a bumpy one, as markets start to price higher levels of risk once again. The Bank of England continues to be further behind in this rhetoric, with most of the political uncertainty being borne by moves in sterling’s exchange rate.

Central banks continue to remain in unchartered territory and we think they will soon find themselves in the difficult position of ‘damned if they do… and damned if they don’t.’ If they remove monetary stimulus quicker than the market currently expects, then there is a real danger that this is more than a highly indebted global economy can tolerate, and certainly more than fragile financial markets can bear – just look at how stock markets reacted in February.

However, if they shy away from tightening financial conditions sufficiently, fearful of the impact on both the financial and real economy, then inflationary pressures are likely to build and both equity and bond markets could sell off regardless.

Jenny Renton is an investment manager at Ruffer

This article is sponsored by Ruffer