The end of 2017 saw a continued global economic recovery, with both advanced and emerging economies showing their strongest growth in five years. The exception was the UK, where weak productivity growth was behind a downgrade of GDP expectations in the November Budget.

Around 60 per cent of economic activity in the UK is accounted for by consumer spending. Annual spending growth dropped from 5 per cent to 3 per cent during 2017, hitting the transport and communication, hotels and restaurants, and clothing sectors the hardest. Employee wage growth also fell back from a 5.6 per cent growth rate to 3.5 per cent.

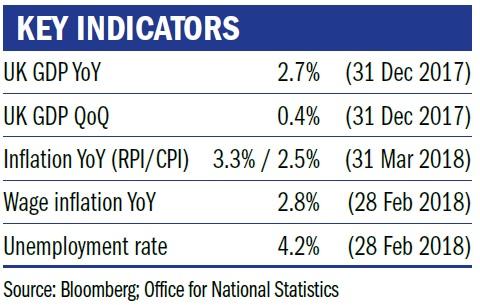

The key to consumer spending is the relationship between people’s income and inflation – their real income. If inflation is above the rate of increase in wages, then people will suffer a squeeze. This was the case through most of 2017 in the UK.

Much of the inflationary pressure was due to the post-Brexit weakening in sterling. This fall in the pound did much to increase British exporters’ competitiveness, but increased the cost of imports, which had a knock-on effect for firms and consumers.

Wage rise on the horizon?

But could the tide be turning? The most recent economic data shows that UK job vacancy postings, an indicator of the health of the underlying economy, are at their highest level in the last 18 years. When there are more jobs than people to fill those jobs, pressure translates to higher wages, which have been volatile or depressed for most of the last five years. We are now at a level of average hourly-earnings growth not seen since the beginning of 2008.

Despite Brexit, political uncertainty and tensions with Russia, there are also signs that the UK consumer is starting to feel more optimistic. Quarter-one figures for 2018 indicated that the wage-growth/inflation gap had closed, and in March we saw a pick-up in UK retail sales despite wintery weather. Overall we saw the fastest pace of growth since September 2017.

What does this mean for the economy and interest rates? In short, we think the short-term pessimism regarding the UK economy is overdone, with higher wages and better consumer confidence likely.

However, we could see a bit more inflation as a result, and if better fortunes do not persist, we expect the UK government will have to take the reins with fiscal stimulus.

Jenny Renton is an investment manager at Ruffer

Charity Finance wishes to thank Ruffer for its support with this article