A public spending review had originally been scheduled to take place alongside the budget this autumn, but the uncertainty surrounding Brexit has jeopardised this time frame. Chief secretary to the Treasury Liz Truss recently confirmed the delay.

Truss followed this with a warning to Conservative Party leadership candidates not to lose sight of budgetary discipline. However, it would seem this fell on deaf ears.

As the leadership race progressed, candidates made eye-catching pledges in the hope of wooing grassroots Tory members. Jeremy Hunt promised to double defence spending, Dominic Raab vowed to cut income tax and Boris Johnson said he would cut higher rate taxes. Most ambitious of all was Michael Gove’s pledge to replace VAT with a lower, simpler sales tax, which would be the largest change to the tax system in decades.

Leaving aside the fact that it would be very hard to push through radical changes in the short term, all candidates were leaning towards more lax fiscal discipline. There is pressure building, both here and abroad, to reduce tax burdens and to increase public spending.

Jeremy Corbyn’s “people’s quantitative easing” hit the headlines a couple of years ago as an example of the latter, and “modern monetary theory” – the current hot topic among economic commentators – proposes that spending should be increased to whatever level is necessary to enable full employment.

Away from austerity

Balance sheet expansion by major central banks via QE over the past decade has been extraordinary. This has led to asset price inflation, without significantly affecting consumer price or wage inflation.

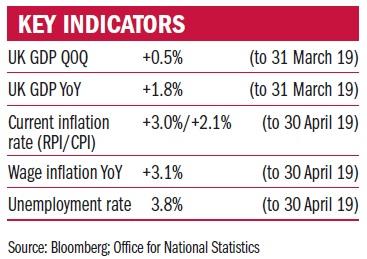

If fiscally expansive policies were enacted in the UK, the increase in spending would serve to raise aggregate demand within the economy, potentially leading to demand-pull inflation. A backdrop of lower taxes and low unemployment would only exacerbate the situation.

There is a tight feedback loop between actual changes to inflation and the effect that people’s expectations have on their spending behaviour and therefore future inflation levels. The latter is the hardest genie to get back into the bottle if the ability to raise interest rates is hamstrung by an extended household debt burden.

Edward Donati is an investment manager at Ruffer

Ruffer LLP is a limited liability partnership, registered in England with registered number OC305288 authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. The information contained in this article does not constitute investment advice or research and should not be used as the basis of any investment decision.

Related articles