Climate change and social inequality are two material and systemic risks facing the global economy and investment portfolios over the coming decades. Market-driven solutions to each issue offer tremendous opportunities for investors. But rather than viewing climate change and social inequality solutions through distinct lenses, investors should approach them via an intersectional lens. This approach involves drawing out the connections between climate change and social inequality and using them to generate actionable investment ideas through an inclusive process.

Climate change is also a social justice issue, given its disproportionate impact on women, people of colour, lower income communities, and developing countries. This article outlines ways in which investors, including those pursuing a path to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, can implement an intersectional approach to climate justice in portfolios, both holistically across themes and within each asset class. It also suggests three steps investors should consider to help ensure that the transition to a low-carbon economy is inclusive and just. Ultimately, we believe all investors would benefit from understanding the risks and opportunities associated with climate justice.

The intersection of climate and social justice

The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989. It describes the interconnected and overlapping systems of discrimination across social categorisations such as race, class, and gender. Climate’s disproportionate impact on the under-represented is a key factor in the discussion of intersectionality.

While the physical and transition risks of climate change are now familiar themes for investors, more focus is needed on the disproportionate impact of climate change on women, people of colour, lower income communities, and developing countries. Climate change acts as a powerful accelerant to existing social and economic injustices and vulnerabilities. This acceleration only further destabilises the broader socioeconomic systems upon which capital markets depend.

Women – particularly historically marginalised women who continue to be affected by the history of colonialism, racism, and inequality – are more vulnerable than men, in part because they represent the majority of the world’s poor and are proportionally more dependent on threatened natural resources. Many lack access to opportunities for improving and diversifying their livelihoods and have low participation in decision-making. Additionally, as climate change reduces crop and forest yields and increases acidification of the ocean, the care burden of household chores such as collecting water and firewood become more difficult, dangerous, and time consuming. This crowds out opportunities for other activities such as education. Extreme heat and humidity, worsened by climate change, also exacerbate health outcomes for marginalised workers in agriculture and construction, reducing labour productivity and further stressing already cost-burdened healthcare systems.

Because of racial discrimination in environmental policy-making – also known as environmental racism – people of colour are more likely to live near sources of contamination and away from clean water, air, and soil, exposing them to the brunt of the impact of climate change. For example, an outsized number of fossil-fuelled power plants and refineries are positioned in Black American neighbourhoods, leading to poor air quality and heightened negative health consequences.

This proximity to pollutants of all kinds dramatically increases incidences of cancer, asthma, stroke, and heart disease, thus putting a strain on health and economic systems across the globe.

Climate justice investment opportunities

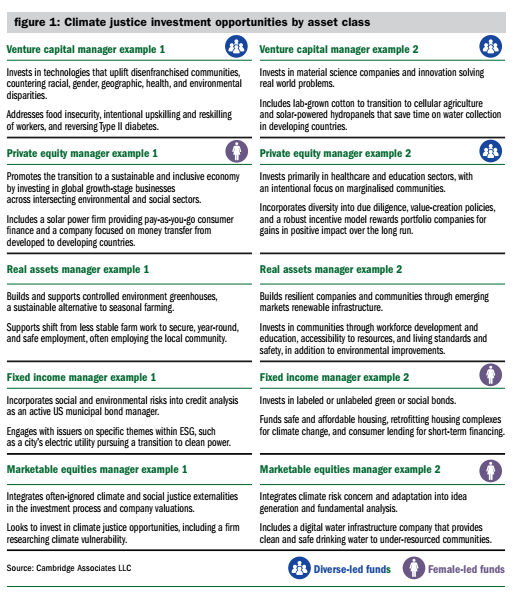

Recognising the scale of the climate justice challenge, public policy and philanthropy will play an important role. But market-driven solutions, when properly designed and implemented, can work alongside public commitments to accelerate solutions. The landscape of investable opportunities in climate justice, while still nascent, is growing. Across asset classes, leading managers are intentionally incorporating climate justice into their strategy. Available fund investments are varied and include climate-focused managers with a social lens, social-focused managers with a climate lens, or certain generalist managers with exceptional environmental, social, and governance (ESG) implementation processes. In figure 1, we highlight recent examples from the marketplace for five major asset classes.

In addition, allocators can approach climate justice holistically by considering a single theme across asset classes, geographies, and sectors. A blend of this approach, along with asset class-specific approaches and the engagement strategies we discuss later in this article, should serve investors well. A few examples of climate justice themes that cut across asset classes include the following.

Renewable off-grid energy

Many developing regions will see devastating effects of climate change in the coming decades. Off-grid energy access can provide these communities, and especially women, economic empowerment opportunities. Off-grid energy infrastructure can mitigate climate risk by reducing the demand for fossil fuels, such as diesel and coal, while also helping to avoid blackouts caused by extreme weather events. There are investment opportunities not only in distributed off-grid energy development and infrastructure, but also microfinance and small and medium enterprise (SME) credit opportunities and corporate equity investments in areas such as e-commerce, education, healthcare, and financial inclusion. Through a holistic and multi-asset class approach, investors can power and empower these marginalised communities.

Healthcare

Accessibility is increasingly critical in a society adapting to a changing climate. As extreme weather events grow in severity and frequency, and diseases spread across a warming planet, access to affordable, holistic care is necessary. Innovation funded by venture capital provides opportunities to cure disease and find solutions for reaching previously difficult-to-access populations. Investments in infrastructure, particularly in more rural and disenfranchised geographies, can improve care and emergency response. Investors can also access the sector through municipal bonds in hospitals and other essential services, such as clean water and digital infrastructure. Additionally, the healthcare sector can offer a defensive portfolio diversifier as life sciences companies and real estate tend to hold up in economic recessions.

Digital infrastructure

As remote working and learning continue, digital infrastructure investments in fibre, wireless networks, and middleware (accessed via real assets and private equity) and at the application layer (via venture capital) can help accelerate digitisation and expand access, especially for women and underserved communities. Better digital infrastructure can also improve health outcomes by providing access to advances in low-cost telemedicine. At the same time, some of these infrastructure investments carry “smart city” applications, which can improve both the energy efficiency as well as government fiscal positions. In a systemic approach, this one seemingly narrow theme can cut across asset classes all while playing a role in addressing social and environmental pain points.

Other intersectional thematic opportunities with a climate justice lens include water and food systems, workforce transition and development, care burden, and financial inclusion.

The role of allocators

Allocators can more intentionally embed consideration of climate justice issues by taking three key steps: (1) make climate justice and a just transition priorities in the investment policy statement (IPS); (2) engage with fund managers on the topic of climate justice; and (3) put climate justice and inclusion at the centre of the investment selection process.

1. Prioritise climate justice in the investment policy statement (IPS)

All investors can use the IPS to outline purpose, priorities, and principles. Institutions and families can use the policy setting process to educate stakeholders, commit to further learning on key issue areas, and, once set, communicate the approach to advisers and managers.

Many institutional investors have made a commitment to transition to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions in investment portfolios by 2050 or sooner to meet the objectives laid out in the 2015 Paris Agreement. As the investment policy roadmap toward net-zero is codified, concerns regarding climate justice and the just transition should also be incorporated into the discussions and policy statement.

A just transition is the idea that as the world moves from an extractive to a regenerative economy, the transition must be inclusive and equitable, and it should not create stranded assets, workers, or communities. For example, displaced workers from the global high-carbon industry – such as coal miners, oil & gas workers, and meat producers – are heavily composed of low-to-middle income, rural communities. They will need intentional workforce development and reskilling for a just transition to occur systematically.

While we expect the shift to a less carbon-intensive economy to be a net positive for the economy and society at large, there will be significant transitional challenges for key sectors, communities, and countries. Investors can align their investment policy to work toward a just transition, which should enhance their understanding of systemic risk and help them identify promising opportunities.

2. Engage with fund managers on climate justice

Fund manager engagement is an important portfolio management tool and key to a successful intersectional approach. Questions around incorporation of climate justice factors in the investment process can help allocators to assess manager awareness of risks and opportunities, and avoid investments that may conflict with investor goals. Engagement with fund managers can also serve to improve consideration of climate change and social inequality across the industry. Allocators should consider the following questions as they engage with investment managers:

- How are ESG risks and opportunities integrated into the investment strategy and process? Do you integrate ESG in deal documentation, post-investment action plans, and improvements to underlying investments for this strategy?

- How does your strategy invest to create positive social outcomes and limit negative social externalities of climate change?

- Do you assess how underlying investments are accounting for the impacts of climate risks on employees and communities as it relates to business activities? Additionally, do you consider these factors in assessment of market opportunity and target end users of your investments?

- How do your portfolio companies incorporate and measure the effect that climate solutions have on women and people of colour?

- How are you incorporating externalities from the transition to a low-carbon economy? Examples include workers’ rights, land use, employment, and whether the process of creating materials for a low-carbon economy is toxic and affects the local community.

- How do you use your role as an investor to encourage underlying companies to consider risks and opportunities of climate justice through shareholder engagement, proxy voting, board seats, etc?

- How does your firm incorporate diversity, equity, and inclusion in your operations and investment practices?

- How do you address implicit bias in decision-making in both investment and management contexts?

- Do you have the cultural competency to address the needs of racially diverse communities?

- What evidence can you offer that the solutions or products you are providing are grounded in the needs of the community?

While these questions won’t apply to all managers and this list is not exhaustive, we believe they should help many allocators to find managers taking an authentic, intersectional approach.

3. Select inclusive investment managers

Allocators looking to invest with an intersectional lens should also look at their own teams and decision-making processes to ensure they are being as inclusive as possible. A diversity of thought and talent requires different perspectives, different points of reference, and different experiences. Homogeneous teams are more susceptible to missing opportunities and being blind to some risks. Investment teams that prioritise diversity and mitigate bias as part of their process have a greater opportunity for higher investment returns.

This philosophy extends to seeding or backing emerging talent early. Investment teams and fund managers from underrepresented backgrounds may see climate justice opportunities and risks that others do not, due to lived experiences and differentiated networks. Women and communities of colour are powerful agents of change regarding issues that disproportionally affect them, and investors benefit from investing in diverse managers, entrepreneurs, and communities. As such, intentionally backing diverse and emerging talent investing in inclusive climate solutions is one powerful way to reflect a climate justice lens in a portfolio.

Conclusion

The longer-term costs related to climate change and social justice should be incorporated into all investing decisions. Pursuing net-zero without full consideration of these runs the risk of exacerbating social and economic injustices and increasing portfolio risk. Ultimately, a holistic climate justice approach deliberately acknowledges that these risks and opportunities are intersectional and cannot be separated. Investors that pursue a deeper understanding of this intersectionality may enhance the long-term climate, social, and financial resilience of their portfolios, benefiting stakeholders.

Deborah Christie is managing director, public equities, Madeline Clark is investment director, sustainable and impact investing, and Eliza Noyes an associate director, sustainable and impact investing, at Cambridge Associates

Charity Finance wishes to thank Cambridge Associates for its support with this article