The Shaw Trust is the top performing charity in this month’s review, reporting a 27 per cent increase in income to £132.1m in the financial year ending 31 March 2017. The increase resulted from the acquisition in 2016/17 of Scottish mental health charity Forth Sector and the transfer of three schools into the wholly-owned Shaw Education Trust, which became a multi-academy trust in 2014.

The Shaw Trust, which helps disabled and disadvantaged people into employment and independent living, has grown rapidly in recent years. It acquired the Disabled Living Foundation and a majority stake in CDG-Wise Ability in 2014/15, and has since acquired five schools, bringing its total number of schools up to eight.

All this is dwarfed, however, by its most recent deal – the November 2017 acquisition of the Prospects Group. Although the recency of this move means that the new income is not yet reflected in our Index data, the Trust has stated that its annual revenue has been boosted to around £250m and staff numbers have increased from 1,800 to 3,200. According to Shaw Trust CEO Roy O’Shaughnessy, the deal marks a significant step in “our journey to transform the lives of one million young people and adults each year by 2022.”

Another top performer in the quarter under review, which owes at least some of its growth to acquisition, is United Response. The disability charity reported an 18 per cent increase in income to £93.7m in the year to 31 March 2017.

The acquisition of Devon-based charity Robert Owen Communities accounted for around 30 per cent of this increase. The balance was provided by growth in contract income, mainly from statutory authorities, which increased by 13 per cent in 2016/17 to £87.9m. According to United Response chair Maurice Rumbold, the success rate in winning new contracts improved thanks to the charity being more selective. “All quality, operational and financial criteria must be met before bidding for, and accepting, new business.”

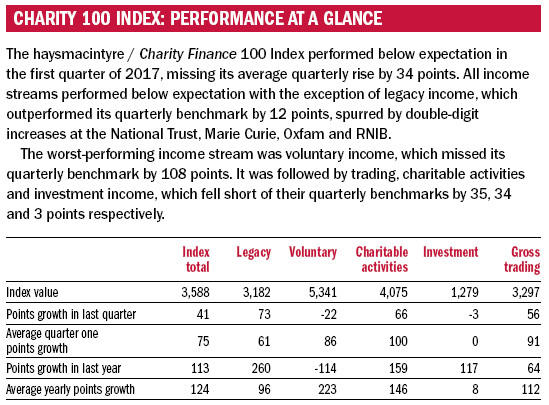

These significant income gains have, however, been offset by falls at other members of the haysmacintyre / Charity Finance 100 Index, resulting in overall below-par performance in the three months to 31 March 2017.

Motability, for example, reports a 21 per cent fall in income to £53.3m, resulting largely from a £7.6m drop in grant funding from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) for specialised vehicles, which came to an end on 31 December 2015. The cessation of DWP funding is part of the government’s proposed transition to the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) scheme, which was introduced in 2013 and is intended to replace the Disability Living Allowance for the funding of vehicles for disabled people by the end of 2019.

International charities

As the government negotiates the UK’s exit from the European Union following the 2016 EU referendum, it is timely to consider the likely impact of Brexit on charities which operate across borders.

Across the Charity 100 and Charity 250 Indexes, there are 40 UK-registered charities which have an explicit international remit. They range from Save the Children with annual income of almost £400m to The Halo Trust with just over £25m.

They also span a wide range of sectors. They include international aid and relief agencies such as Oxfam and the British Red Cross; religious charities such as Islamic Relief Worldwide, Christian Aid and the Catholic Agency for Overseas Development (Cafod); charities that focus on specific groups such as Unicef and HelpAge International, and those that focus on specific health and environmental issues such as World Vision UK and WWF-UK.

With the terms of the UK’s departure from the EU still so uncertain, it is not easy for charities to assess the impact of Brexit on their operations in any great detail. That all said, this very uncertainty is having an impact on the sector in the shape of foreign exchange volatility, which has over the last 18 months eroded the overseas spending power of sterlingdenominated funding.

As Karen Brown, chair of Oxfam Great Britain, observes: “The massive devaluation of the pound following the vote to leave the EU put a real strain on programme finances in 2016/17 and ultimately meant our money did not go as far as we planned for it to.”

Exposure to the devaluation of sterling does, of course, vary according to the currencies held. Mercy Corps Europe reported an increase in foreign exchange reserves from £1.4m to £3.7m in the year to 30 June 2016.

As a large proportion of the Scottish charity’s balance sheet is not denominated in sterling, devaluation led to a large unrealised gain. This outweighed the losses realised by having to exchange sterling and euros for US dollars to settle with creditors within the Mercy Corps International group at rates 10 per cent lower than when the debt was incurred.

Similarly, trustees at Sightsavers International report that the revaluation of its US dollar holdings mitigated the impact of sterling’s devaluation in the year to 31 December 2016. They caution, however, that this will be much harder to achieve when US dollar hedges at pre-Brexit vote levels have expired.

Predictably there are also concerns over the ability of UK charities to access European Commission (EC) funding after Brexit. “Questions surround our long-term eligibility as a UK-registered charity to access key European Union development and humanitarian funds, which currently account for approximately 9 per cent of our global funding,” says David Causer, trustee at HelpAge International.

Sightsavers International is more sanguine, commenting that it will still be able to access EC funding from its other European offices, but adding that “EC funding may well be in much shorter supply once the UK withdraws its funding from EC development, given that it is currently a major contributor.”

According to Simon O’Connell, executive director at Mercy Corps Europe, the risks to charities by Brexit are not just financial. “The longer-term impact of Brexit on the UK’s international standing is harder to quantify but potentially more worrying. In recent decades the UK has played an important and generally progressive role in global policy on development issues, humanitarian response, climate policy and global security.

“This comes in part from the UK’s roles in multilateral organisations – including the EU – and in part from its wider ability to contribute through diplomacy, trade and research. As the UK’s role in Europe shifts and more focus is placed on dealing with the domestic implications of Brexit, we risk losing that positive wider role.”

Brexit issues for international charities

Murtaza Jessa, partner at haysmacintyre, takes a closer look at issues for international charities.

There are a number of ways in which Brexit will affect charities, and the effects will be felt disproportionately across particular sub-sectors of charities and causes. Charities that work internationally may need to consider a number of potential risks to their activities.

EU and other funding

UK charities receive EU funding of over £250m a year. Replacing EU funding will not be straightforward. While many large international charities have group and affiliated charities worldwide, including representative charities in EU countries that will continue to be eligible to access EU grants, there is a strong possibility that the funds available for EU grants will be substantially cut as the UK has been the third biggest contributor to the EU after Germany and France. Brexit will therefore leave the EU with a much reduced budget to fund charities.

In 2016, following the EU referendum, the Treasury pledged to continue to support projects agreed up to the point at which UK departs the EU, subject to them being value for money and in line with the government’s strategic priorities.

In the 2017 Conservative party manifesto, there was a pledge to create a shared prosperity fund. This may well mean that some charities get additional support, whereas other charities – including those that have so far attracted EU funding – may not be in favour.

In addition to direct funding from the EU, substantial sums have been received by charities from various European funds. These include the Swedish International Development Fund (SIDA), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Norway, the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland and other European government funds. A good proportion of these funds have been for restricted purposes, but funders such as SIDA have provided substantial core grants to the UK-based charities that work internationally. While they might still do so after Brexit, there is uncertainty as to whether they may favour charities based within the EU.

Foreign exchange

Moving from the future to the present, the biggest impact of Brexit felt by many international charities to date has been the effect of the weaker pound. The local currencies of the countries in which international charities operate are pegged mainly to the US dollar, whereas funds are received in pound sterling for UK grants and donations. This means that charities have had to reduce their spending in the beneficiary countries or find additional funds.

Diane Sim highlights Oxfam as being one of the charities affected by this on page 47. Another example is Save the Children International, which states that it lost the equivalent of $26m for 2016. They are far from alone; the weaker pound has affected some smaller charities even more when measured proportionately.

European staff

Analysis by NCVO shows that nearly 5 per cent of the voluntary sector’s workforce are non-UK EU nationals. Even if the negotiations reached on Brexit allow Europeans already working in the UK to remain here, Brexit is likely to affect the ability to retain and recruit replacement staff when existing staff move to different jobs.

Structure

While there are a few international charities that have set up affiliated charities in Europe as a result of Brexit (the Netherlands being popular for some objects), overall we have not seen very many charities taking this course of action. This could be because transactions would need to be consolidated into the UK group accounts if control is maintained, and because while any funds generated by the European charity could be sent to the country of work, it would be difficult to use them to fund UK core costs. The entity set up in Europe would need to operate independently with its own trustees and directors to be effective.

Conclusion

Since adoption of the new SORP, charities have had to disclose their key risks as part of their trustee report. Interestingly, the 2016 accounts filed by a number of international charities did not highlight potential risks of Brexit. This may mean that while the risks are included in the risk register, other risks are considered more prevalent at this point. The omission may also be because charities want more clarity before assessing the impact of Brexit upon them.

Where charities are assessing the risk of loss of income, they should conduct sensitivity analysis and consider the impact on their income if European funds are not replaced in full. Corrective actions may be necessary on some programmes. In many cases, the country programme may need to consist of projects rather than field offices. The flexibility of reducing the scale or in some cases not renewing the programmes should be assessed unless there is an appetite and resources to continue with the programme where the previous funds are not available.

It is clear from the attitude of many charities that the last recession has prepared them to cope much better with uncertainty and adopt change when required. Let’s hope that politicians all over Europe have the agenda to make a difference throughout the world and work together on common issues.