“We are in the midst of a collective act of global, social evil which is unprecedented in all of history. We spend more time measuring it than trying to stop it. We don’t need any more data to tell us how bad it is, we need to understand how change works” Clare Farrell (a founder of Extinction Rebellion).

While this comment is alarming, it frankly has a lot of truth to it. Before focusing on what investors can do, I wish to start off with some of the data just to reinforce that 2050 didn’t come from nowhere, and the importance of interim targets as well.

The data does not paint a pretty picture

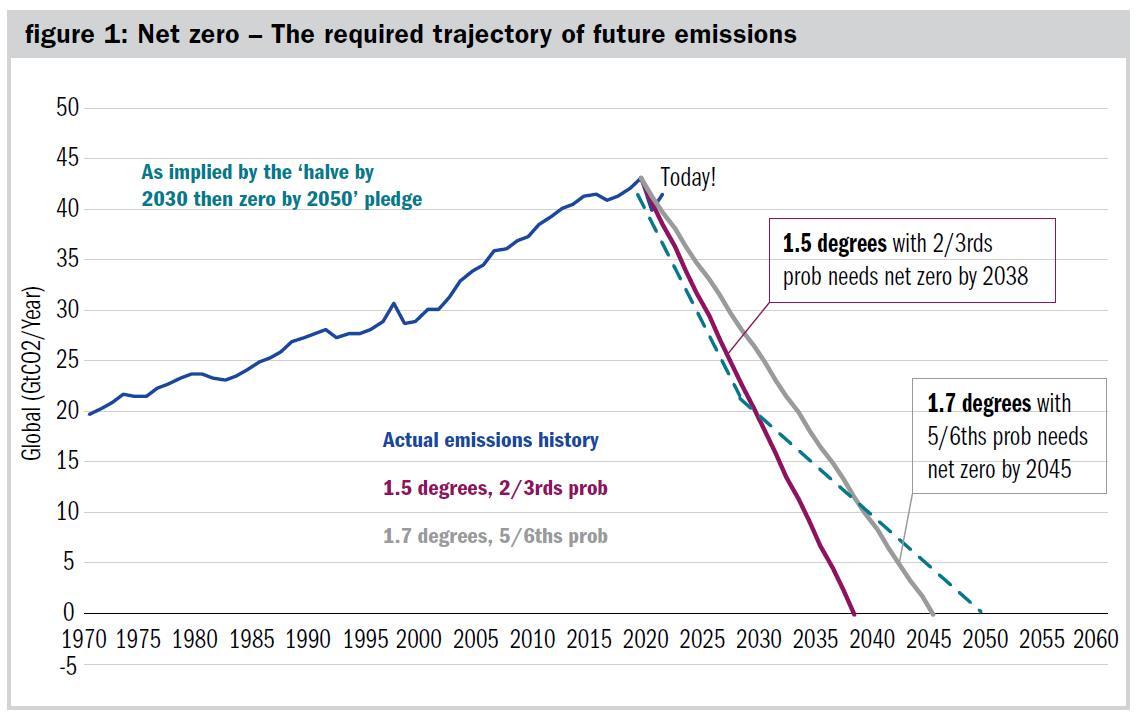

The goals of the Paris Agreement are to “limit global warming to well below 2, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels”. What do those words really mean in terms of a practical goal? The way I interpret them is that we want a reasonable probability, say two-thirds, of limiting to 1.5 and a rather higher probability (say five-sixths) of at least staying well below 2.0. I interpret well below 2.0 as around 1.7. I don’t think those probabilities are very ambitious given the existential risk involved.

So how do we do that? I did a bit of number crunching based on the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment report, AR6, released in August 2021. It provides estimates of the remaining carbon budget that can be burned to have a certain probability of staying below a certain temperature, like the examples I mentioned above. If we combine this with where emissions actually are today, we can work out how long that budget will last if emissions decline in a straight line from here. In figure 1, there are two such lines; one for 1.5 degrees, which takes us to 2038 and one for 1.7 with higher probability which takes us to 2045. So 2050 doesn’t look so comfortable after all.

That’s why Paris-aligned 2050 pledges come with another stipulation that emissions must decline 50% by 2030 (eight years only!). I drew this as a green dotted line. You can see that the steep initial decline from a halving by 2030 is incredibly important in a path even vaguely consistent with limiting temperature rise to around 1.5 degrees.

And if you don’t believe we can do that in less than 10 years, then the net-zero target needs to be a fair bit sooner than 2050. Trouble is, it is not that we aren’t reducing emissions fast enough, we are actually going in the wrong direction. Emissions are still rising. The scale of what needs to be achieved in the next eight years is just gargantuan as of course will probably be the consequences of not doing so.

The investment landscape for net zero is challenging

We generally advocate moving fast to reduce climate risk in portfolios, purely from an investment perspective. Why? Because companies are taking insufficient action on climate change, as witnessed by continually rising emissions. If voluntary action is not working then we will increasingly see regulation, taxation and litigation. This will increasingly bear down on the valuations and profitability of businesses with substantial emissions, especially if they are laggards in planning for change.

Thinking more broadly, having a portfolio that is net zero is meaningless if others do not. Rebalancing to remove carbon from a portfolio will have zero impact on carbon in the atmosphere, because these assets were simply sold on to other investors. Net zero is an idea that only makes sense at a universal global level, so investors with net-zero ambitions need a portfolio that is both aligned with net zero by avoiding the losers and investing in the winners, and is contributing to net zero at a system level.

Focusing a portfolio too rigidly on reported emissions can lead to poor allocation decisions from both a climate and investment perspective. This is because of the way investors account for portfolio emissions.

For example, selling high-carbon assets to other investors results in no immediate change in real-world emissions, despite having a material impact on reported portfolio emissions. Conversely, investing in real-world efforts to reduce carbon emissions can have a slower (or even negative) impact on portfolio emissions, so investors should balance emission reductions with exposure to climate solutions. High-emission industries such as steel, cement, power, and transportation need investors’ encouragement and capital to reinvent themselves with green technologies.

Real-world action by underlying companies will reduce portfolio emissions more slowly than rebalancing. But it will have substantial and tangible impact on real-world emissions. For example, consider one equity fund investing entirely in climate change mitigation and adaptation solutions. Investments include solar and wind power equipment makers, an electric bus maker, and energy efficiency–focused industrials. Portfolio exposure to environmental solution revenues is 6.5 times greater than its index, but the current carbon emissions are also 2.3 times the index, albeit with a rapid downward trend.

The current annual emissions are a poor proxy for the whole-life net-zero contribution of carbon-avoiding or carbon-removing goods and services, as well as for assessing whether they are good investments in a decarbonising world. Emissions reductions should be balanced, therefore, with exposure to climate solutions in a pragmatic way. Note also that you may not be having any impact in the real world by just purchasing the investment in the secondary market, as opposed to funding a new greenfield asset.

The second step to real-world change is pushing all financed companies to reduce their emissions. This means encouraging and requiring all companies in the portfolio to adopt their own credible science-based net-zero plan, and large asset owners and investment managers lobbying and voting directly. For smaller investors, it means requiring their investment managers to do so.

It might seem a Herculean task, but remember emissions are usually concentrated in specific managers, sectors, or even individual assets. For example, the utilities, materials and energy sectors make up just 11% of the MSCI ACWI Index weight, yet contribute 83% of emissions. Ten stocks, comprising a mere 0.8% weight, account for 19% of emissions (data from MSCI ESG Research LLC carbon analysis on indexes as of 31 March 2021).

If you prioritise the major sources of emissions, you can cover most of the ground with a relatively manageable number of companies. For an example, Railpen’s 2021 net-zero strategy identified only 44 companies to engage with in its giant £30bn+ portfolio. Signatories of collaborative engagement groups such as Climate Action 100+ will find that some engagement targets are already covered here.

A key task for investors in 2022 and beyond will be to give these engagement efforts more focus and teeth. Corporate climate plans need all of the following: effective disclosure; short, medium and long-term targets; and an effective action plan, backed up by aligned executive compensation and capex plans. Investors should be prepared to vote against boards failing to deliver an adequate plan. Investors should also consider whether an investment manager not taking this action on their behalf is still appropriate for their portfolio.

How can investment advisers help address the issue?

Alongside engaging with companies and targeting lower portfolio emissions, institutional investors, including charities, can make an outsized positive contribution by backing innovation and investing in transformative new low/no carbon technologies and business models.

This has been further supported by the pledge of 12 of the most prominent investment advisers, including Cambridge Associates, to the Net Zero Investment Consultants Initiative (NZICI) early in 2021. The NZICI sets out actions that investment advisers will take to support the goal of global net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner, in the context of legal and fiduciary duties and specific client mandates.

A number of these pledges have significant ramifications on how advisers will need to engage with their clients including:

1. Integrate advice on net-zero alignment into all investment consulting services as soon as practically possible and within two years of making this commitment.

2. Work with institutional asset-owner clients to identify the investment risks from climate change, highlight the importance of net-zero alignment and, where applicable, support clients in developing policies that align their portfolios to a net-zero pathway.

3. Support efforts to decarbonise the global economy by helping clients prioritise real economy emissions reductions, reflecting the target of 50% global emissions reduction by 2030 or sooner using existing decarbonisation methodologies.

4. Assess and monitor asset managers on the integration of climate risks and opportunities in their investment decisions and stewardship and reflect this evaluation in client recommendations.

We see these pledges as just the start and over time we will be encouraging them to go further.

Conclusion

Net zero is a goal that applies to the entire economy. Either we all succeed, or nobody succeeds. However, as stewards of significant portions of capital our role in the future of the planet remains a vital one.

Simon Hallett is head of European foundations and endowments at Cambridge Associates

Charity Finance wishes to thank Cambridge Associates for its support with this article

Related articles