The last year has seen the challenging backdrop for charities continue. Inflation remains a universal concern as charity beneficiaries endure the cost-of-living crisis, and lower levels of returns and pressure on charity finances are widespread issues.

Now in its 10th year, the Newton Charity Investment Survey has uncovered insightful long-term trends, particularly in relation to charities’ views about the world around them.

Charities are becoming more concerned about the threat of climate change, and their opinions on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues more broadly are changing.

ESG considerations

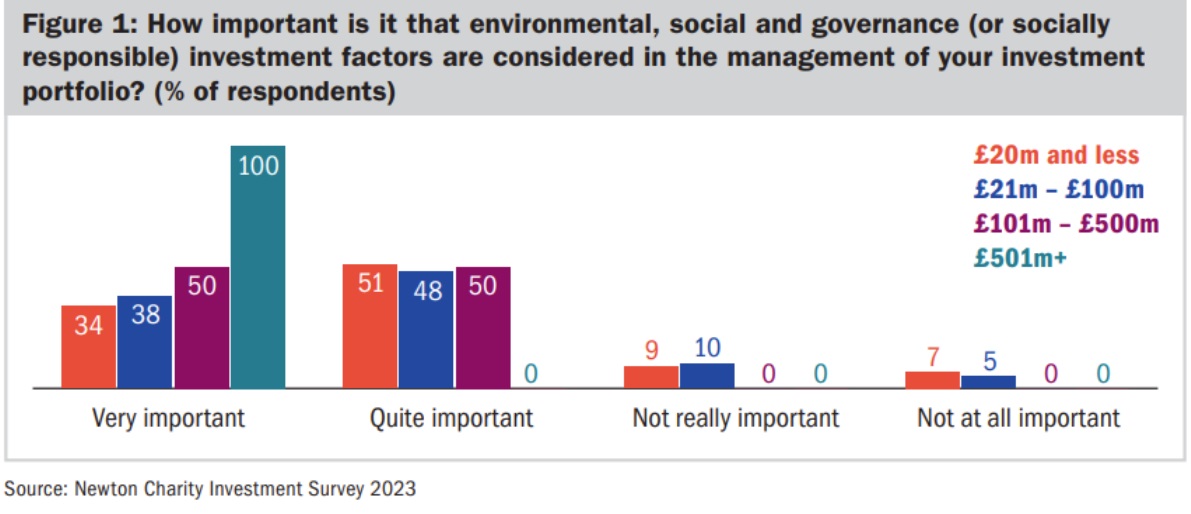

ESG issues remained a key concern for charities in 2023. The total percentage of charities classifying ESG factors as very important or quite important in the management of their investment portfolios has stayed relatively stable at a combined 86%.

However, 2023 shows the first decline since 2018 in the percentage of charities which think that ESG factors are very important in the management of their investment portfolios. That figure now stands at 37% – lower than at any other point in the last five years, though still above pre-2019 levels.

Breaking responses to this question down by charity size does show a clear gap in terms of the consideration of ESG factors. The largest charities with assets under management (AUM) of over £100m are significantly more likely to rate the consideration of ESG as ‘very important’, perhaps reflecting the greater sophistication of investment considerations or greater scrutiny on the operations of larger charities, and the associated reputational risks.

Exclusion policies

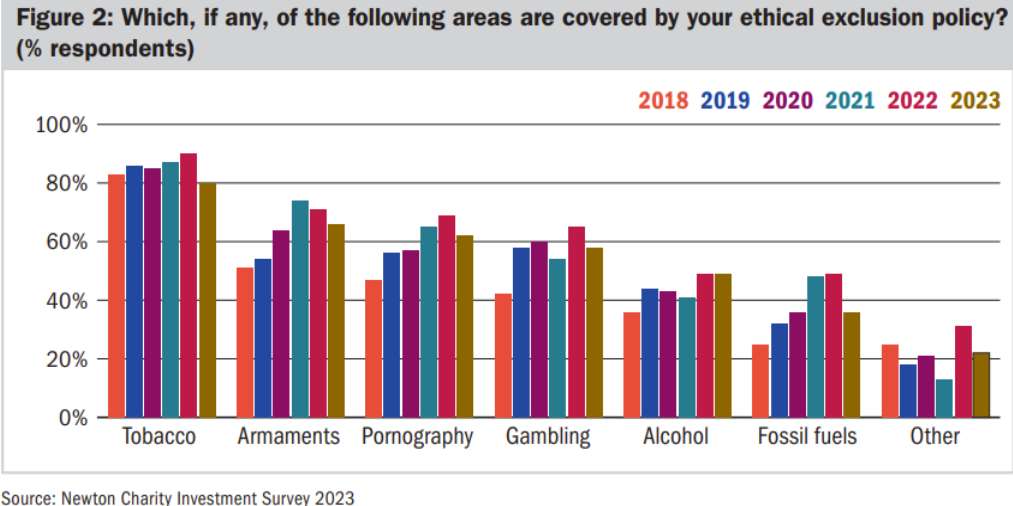

After several years of relative stagnation, the use of ethical exclusions has risen this year for the first time since 2020. Ethical exclusions involve charities prohibiting investment in companies with material revenues from areas such as tobacco, alcohol, gambling and other industries.

The use of exclusions across charities now stands at its highest ever level, with 64% of charities implementing some form of exclusion policy when it comes to their investments. The picture is not the same across the entire sector, and the smallest charities with AUM of less than £20m are far less likely to have such a policy.

Perhaps this is owing to those charities’ lack of time to discuss exclusions or their lack of power in implementing such a policy. Every area of exclusion, with the exception of alcohol, has seen a decline in the proportion of charities covering it within their policy.

The two areas that have seen the most significant reductions in the proportion of charities excluding them in their portfolios are fossil fuels, falling from 49% to 36%, and tobacco, dropping from 90% to 80%. The exclusion of armaments has seen a second consecutive year of decline, perhaps owing to returns in this sector improving as a result of Western backing of Ukraine in its defence against Russia and the recognition of the need for Europe to defend itself.

Therefore, perhaps exclusion policies themselves are being re-evaluated in light of the deteriorating economic backdrop and stronger returns from excluded sectors.

Charities may be taking the opportunity to hone their exclusions to target specific areas that clash with their mission and values, reflecting the recommendations of the Charity Commission’s revised investment guidance (CC14). CC14 invites charities to consider whether they should adopt an ethical, socially responsible or mission-related approach to investment.

Engagement versus divestment

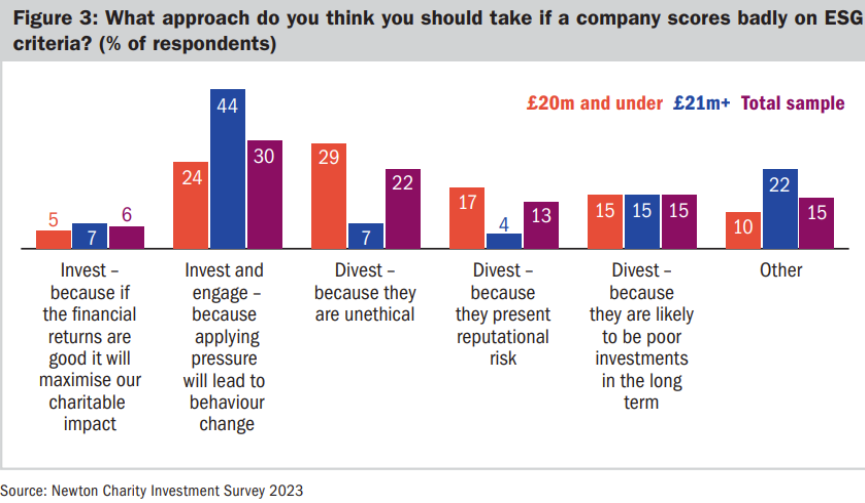

When it comes to the application of ESG principles, we are seeing charities becoming polarised on how best to approach companies that are underperforming on ESG criteria. In our survey, engaging with companies with weaker ESG performance was the largest single response, and was chosen by 44% of larger charities.

However, we offered three divestment options with three rationales (because they are unethical, because they present reputational risk and because they are poor investments in the long term) and, overall, divestment was selected by half of respondents and 61% of smaller charities.

This difference by size may reflect the confidence that large charities have that their views and opinions carry weight with their investment managers and, by extension, with company boards. Smaller charities, which have fewer resources, may be less confident in challenging their investment managers to engage on their behalf.

As a result, we think there is an opportunity for investment managers to help their smaller charity clients feel more connected to the engagement process and build confidence that their views matter and, in aggregate, can influence companies. We see engagement as being a critical part of the value an investment manager delivers both in achieving returns and in improving the parts of the environment and society affected by company actions.

There is more agreement in the view that engagement is the best approach for ensuring that climate-change factors are considered within the management of charities’ portfolios (as opposed to divestment or something else). The selection of engagement increased from 59% of charities in 2022 to 66% in this year’s survey.

Nevertheless, organisations are increasingly viewing their position on climate change and investment in fossil-fuel production as an ethical issue, and are considering exclusion policies. This builds on the announcements this year by the Church Commissioners and the Church of England Pensions Board about their decisions to disinvest from fossil fuels.

Our survey revealed that an increasing number of charities have debated fossil-fuel-free investments, up to 62% this year, though more than half have taken no action to exclude fossil fuels following this debate.

Engagement in practice

We believe responsibly managed companies are better placed to achieve sustainable competitive advantage and provide strong long-term growth. We use three main stewardship tools to improve the management of companies: engagement, voting and advocacy.

We define engagement as the purposeful dialogue we have with companies to add value or reduce risk. This means setting clear objectives requiring actionable change for our engagements and tracking and measuring progress.

We believe engagement is distinct from investment research and information gathering. Higher numbers of low-quality engagements do not equate with better stewardship. Our focus is on achieving the progress or change that we set out as an objective, which we believe should contribute to better investment outcomes for clients.

Through our investment research process, we identify the ESG risks and opportunities faced by a company. Companies which we do not consider to be managing these challenges well will become candidates for engagement as improvements here could improve our, and hopefully the market’s, valuation of a company.

Companies are then prioritised for engagement based on a combination of factors that include the materiality of the issues to be raised, our likelihood to meaningfully engage, the aggregated amount of our invested interest and, where relevant, our past engagement and voting activity. The following example demonstrates how this has worked in practice when engaging with Unilever.

Engagement case study: Unilever

Despite being a leader in ESG and having a purpose-driven approach to business, we considered the Unilever’s disclosures around nutrition to lag those of other leaders in the food space.

The company had fallen behind retailers such as Tesco and Sainsbury’s and there was limited transparency provided for investors to understand how its sale of unhealthy products aligned to its purpose. Its focus on condiments and ice cream also makes it more highly exposed to risks based on its product offering.

We have had regular engagements with Unilever on nutrition, changing consumer demand and product shifts over a number of years both directly and through the Healthy Markets Initiative, and encouraged the company to report on its product profile using a government-endorsed nutrient profiling model.

We believed the regulatory direction of travel was towards standardised adoption of this tool, and the business would be negatively affected if it instead adopted its own nutrient profiling tool which it seemed inclined to do.

We stressed the benefit for investors from the overall transparency provided by these disclosures in terms of better comparability and the ability to integrate them into investment decisions. During the year, Healthy Markets filed a shareholder proposal which was ultimately withdrawn following a response by the company. We remained involved in discussions.

Outcome: We were pleased to see Unilever’s announcement in March 2022, and its subsequent disclosures in October 2022, on the nutritional profile of its products based on six nutritional profile models, covering 16 strategic markets, based on both volume and revenue. This reporting is best in class and we hope it will raise the bar across the industry in disclosing the proportion of healthy products within a company’s product portfolio versus government-endorsed models.

Engaging with the engagers

Faced with the current challenges, charities will wish to ensure they are getting as much value as possible from their relationships with investment managers.

In many cases they will depend on managers to engage with the companies that they are invested in. We believe that it is crucial that managers communicate how engagement works in practice and that charities, regardless of size, feel informed and involved.

Questions to ask your investment manager

- What is the investment manager’s approach to stewardship, including engagement, voting and advocacy?

- How does the manager measure and report on stewardship activity, including engagement progress?

- Does the manager work collaboratively with other stakeholders?

- What engagement escalation methods does it use if it feels a company is insufficiently responsive?

Nico Aspinall is sustainability advocate at Newton Investment Management

Charity Finance wishes to thank Newton for its support with this article

Related articles