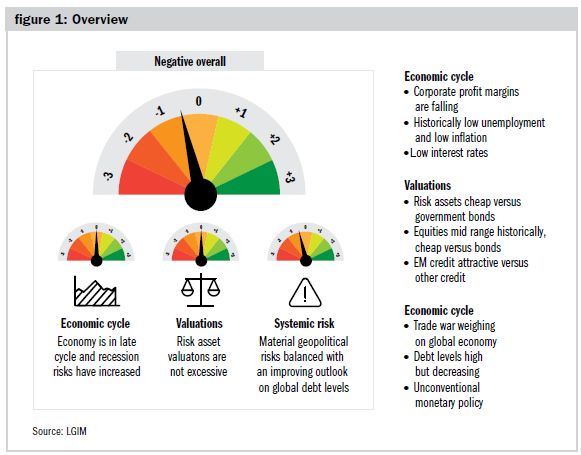

Throughout 2019, we have pointed out that investors faced a murky macroeconomic outlook, with a number of risks on the horizon, even though markets continued to be supportive. The outlook is now somewhat clearer – in that the risks have grown in scale.

Our economists now see a 30 per cent chance of a global recession in the next 12 months. This is the highest probability since the start of the cycle in 2009, yet US equities are within spitting distance of their record highs.

We are increasingly convinced that investors are in a late cycle period, when the buy-on-dip strategy of the past few years might prove less effective. Consequently, we have reduced our equity stance to a slight underweight or negative position from neutral.

Weak earnings

A darkening economic outlook translates into expectations for corporate earnings, which are disproportionally impacted by developments in the industrial sector. Manufacturing growth is weak globally – leading us to anticipate US earnings will contract slightly next year.

At the same time, we believe the current perceived deal in the US-China trade war might indicate a temporary peak in optimism. Tensions will probably remain for the coming years.

In the run-up to the US presidential election next year, negative rhetoric on the world’s second largest economy might increase from both Democrat challengers and the incumbent, which will make it harder to reach a long-term agreement with China. That election could result in a sharp swing to the left, with momentum towards the impeachment of Donald Trump a positive for Democratic candidate Elizabeth Warren, whose plans are seen as negative for Wall Street.

Elsewhere, the Brexit drama rumbles on, posing a material risk to the euro-area economy, even if there is a deal. Moreover, a regime shift in economic policymaking in China means we can no longer rely on it to prop up global growth.

Fed support

The US Federal Reserve remains willing to support markets, in the event of a tightening of credit conditions. However, unlike in December 2018, quite a bit of accommodation is already factored in by investors – and lately we have seen the central bank do less than is priced, with the recent pause in rate cuts after three consecutive moves. These factors create substantial vulnerability for equities, hence our cautious positioning.

Still, the picture is not completely bleak. The trade conflict could be resolved, especially since Trump requires a positive economy in 2020 to boost his chances of re-election. And, while absolute valuations for US stocks might be a cause for concern, relative valuations versus interest rates are positive.

Should the world economy enter a recession, we expect it to be mild, justifying a market drawdown of about 20 per cent. Any decline greater than this would probably turn us into dip buyers again.

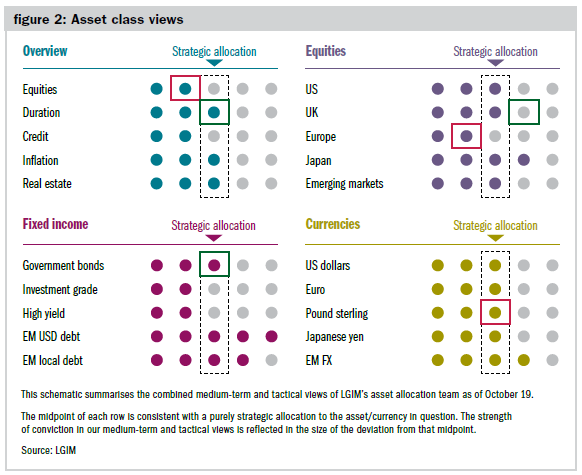

Our views at a glance

A slight negative view on equities – downgraded, both tactically and over the medium term, driven by the escalating US-China tensions weighing on the global economic outlook and our recession indicators having worsened. At a regional level, we still favour Japan relative to the US and have upgraded our view on the UK, thanks to valuations and Brexit risk being fairly priced, in our view.

Remain positive on emerging-market debt – spreads remain relatively attractive and default risks stay low.

Neutral on developed-market government bonds – improved since last time, as our fundamental view has changed, given central-bank actions and the economic environment.

Remain negative on credit – the asset class tends to underperform at this part of the cycle and valuations remain unattractive.

Why ECB easing isn’t enough for euro equities

The European Central bank (ECB) recently unveiled its most meaningful package of stimulus in years – yet we are short or underweight on eurozone equities across most portfolios. While this position may appear counter-intuitive, the investment case is fairly straightforward: euro stocks have performed relatively well this year but, over the same period, our macroeconomic views on the region have deteriorated significantly. This has left us facing the combination of higher prices for European equities and lower expectations for the region’s macro backdrop.

The range of risks for stocks in Europe is broad. We see the probability of a eurozone recession over the next year at around 50 per cent. The likelihood of a no-deal Brexit also weighs on concerns, and could also push the eurozone into recession. The risks to our basecase forecasts for the region have, therefore, become heavily skewed to the downside.

We have long held the view that the eurozone is one of the most vulnerable regions in the world to an economic downturn. This would reveal the structural issues that have worried markets in the past, such as the continent’s lack of central-bank firepower and the institutional challenges it faces in responding quickly and decisively to crises.

Investor sentiment

All of the above would be bearable if the valuations of eurozone equities were unusually low and/or sentiment was particularly bearish. Neither is the case today, though.

Valuations for European stocks, relative to other developed markets, are close to their historical averages. Sentiment surveys may suggest that eurozone equities are far from everyone’s favourite, but they are just as unpopular as UK and Japanese stocks, so do not stand out as offering an attractive discount.

The ECB presents one of the biggest potential risks for this position. A big bazooka policy surprise, such as the expansion of quantitative easing (QE) to include stocks, could boost European equities as it did in early 2015. But former president Mario Draghi’s penultimate press conference at the helm of the ECB did not suggest such a game changer is forthcoming.

What of the easing already announced? In the face of persistent inflation undershoot, a growth slowdown and further downside risks, the central bank is deploying and redeploying a range of policy tools.

There is, however, little that ECB action can do when uncertainty is so high. Can marginally lower rates (a meagre ten basis point cut) really stimulate investment spending or help plug the gap in German exports to China?

So even though the stimulus package delivered in September was slightly larger than we expected, it has neither mitigated the recession risks facing the eurozone nor dimmed our view on its merits as an underweight position.

How long will the global manufacturing slump last?

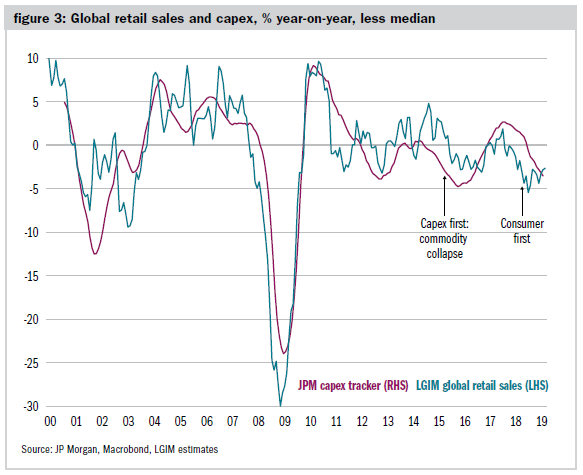

The global manufacturing sector has been stagnant over the past year, with key gauges of activity falling to multi-year lows. This is similar to what occurred after the 2011 euro-area crisis and the 2014/15 commodity crunch.

What has caused the latest downturn? It is tempting to blame the US-China trade war. After all, that has created uncertainty, which in turn should depress capital expenditure. And global business equipment capex growth has fallen by around 5 per cent since its peak compared with a 0.75 per cent decline in global retail sales growth.

However, the capital goods sector is always more cyclical than the consumer goods sector (particularly for staple products such as food).

Indeed, the downturn in equipment capex seen so far looks consistent, with a typical accelerator effect from prior weakness in consumer spending. This is in contrast to 2015, when the collapse of the commodities complex depressed investment even though the global consumer remained resilient.

Since 2018, we have seen a tentative recovery in advanced-economy retail sales, leading some analysts to anticipate a near-term recovery in industrial production. However, Chinese consumption remains depressed as the government stimulus has been relatively muted.

If the weakness in capex is mainly a reaction to previous consumer weakness, then we have yet to see the full effect of geopolitical concerns, such as the US-China trade war and Brexit.

So even if the global consumer holds steady, capital goods production could remain subdued for longer. This would hurt countries like Germany, Japan and Korea, whose manufacturing sectors are particularly exposed to capital goods.

China’s regime change – in economic policy

For the past ten years or so, bad news in China was usually good news: growth shocks triggered a sizeable stimulus, leading to asset-price rebounds in the country, emerging markets and the world more broadly. This regime is now a thing of the past.

Take the trade war. Tariffs announced by the US potentially reduce Chinese growth by 1 per cent, not counting second-round effects on confidence and financial conditions. Yet, despite this large shock, Chinese stimulus announcements have been few and far between.

In addition, the leadership has explicitly ruled out using property to stimulate the economy. This sector was part and parcel of every past stimulus package, as it accounts for 30 per cent of activity when including upstream industries.

Most importantly, China’s policy space has shrunken markedly after a decade of easy policies. Debt has surged by 112 per cent of GDP over the past decade, the current account is moving towards deficit from a 10 per cent surplus in 2007 and house prices look increasingly frothy.

The newfound tolerance for volatility is likely to be asymmetric. Were China to be hit by a positive shock, we believe the authorities would use much of the momentum to clean up balance sheets further and rebalance the economy towards consumption. Therefore, average growth over the next five years should be lower than it would have been without the regime change in economic policymaking.

Implications for commodities

While the medium-term risks of a hard landing decrease as the leadership relies less on leverage to boost growth, short-term risks increase with its rising tolerance for volatility.

Given China’s size – it now accounts for 30 per cent of global growth – the regime change should be felt globally. World growth could become more volatile and weaker on average. In addition, commodity prices would likely suffer; emerging markets as major commodity producers would face headwinds and inflation could remain lower for even longer.

Striking the right balance

This outlook does not shy away from the fact that there is plenty to fret about in the coming months and years, presenting investors with decidedly choppy waters to navigate. That said, there are still some bright spots. If we give serious consideration to the threats and make most of the opportunities, we can still strike the right balance between taking advantage of returns, while managing ever increasing downside risks.

Nancy Kilpatrick is head of non-profit at LGIM

Charity Finance wishes to thank LGIM for its support with this article