Around a third of the largest charities go beyond reporting requirements to publish the exact figure of their highest earner in their accounts and on their websites.

Currently, charities with an income of over £1m are required to outline how many staff are paid more than £60,000, as well as what they are paid, within £10,000 bands.

Analysis by Civil Society News looked at whether the largest 100 charities posted the exact salaries of their highest earner on their websites or annual accounts, which are available on the Charity Commission website.

The research found that 34 of the largest 100 charities published their highest earner’s exact salary, compared to 51 in 2020, when Civil Society News last ran the analysis. However, the largest 100 charities are no longer all the same as in 2020.

NCVO recommends that charities should “set the gold standard” by publishing the exact salary details of their highest paid staff within two clicks of their website’s home page.

Largest 25 charities more likely to go beyond requirements

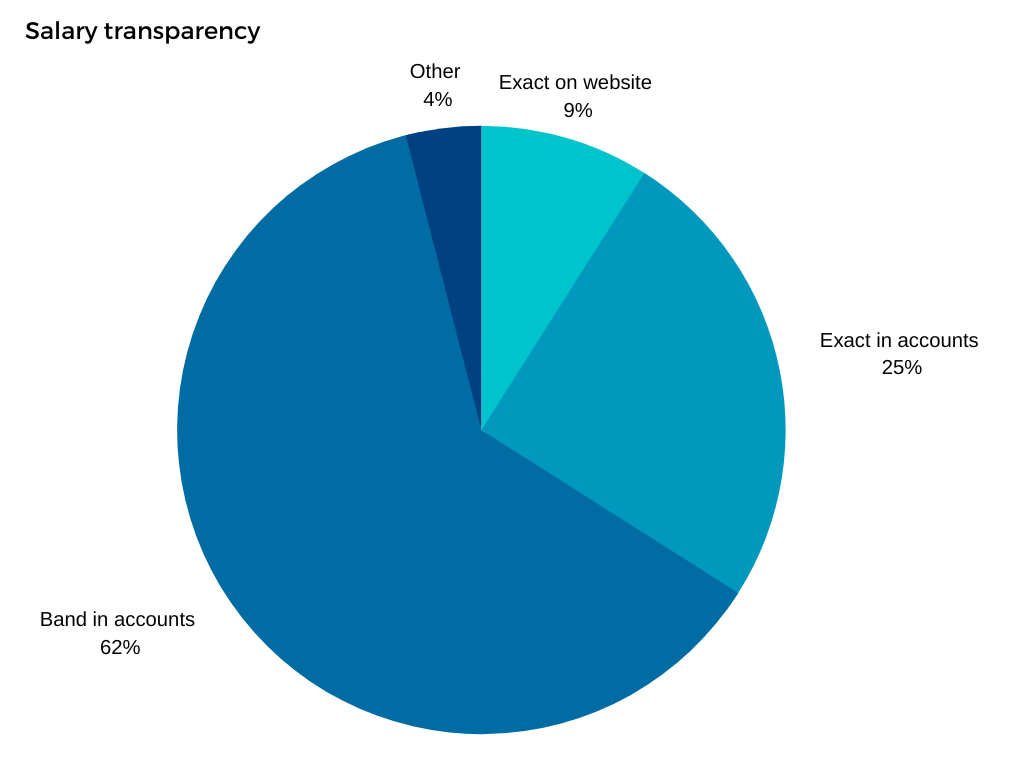

The analysis showed nine of the largest 100 charities published the exact salary of their highest earner on their websites, the same number as in 2020, and a further 25 published the exact figure in their annual reports.

Most of the largest 25 charities published the exact salary of their highest earner, either on their websites or in the annual accounts, with 15 doing so.

An additional 62 of the largest 100 charities published only the salary band of their highest earner.

Meanwhile, four charities did not publish any salary details as they had no staff hired through the charity.

Many charities posted links to accounts on their websites, explaining that salary information could be found there. In the analysis this has not been counted as being directly on a website. Other charities also noted that they had the salary no more two clicks away from their home page, which is recommended by NCVO.

The Charity Finance 100 Index is compiled by Civil Society Media's Charity Finance magazine and ranks the largest charities in the UK by their average income over three years. This was used as the basis for the analysis.

‘We need to set the gold standard when it comes to transparency’

Rebecca Young, lead policy and influencing manager at NCVO, said: “We welcome charities going beyond what is required when it comes to transparency. We are glad to see that the majority of the UK’s largest charities are choosing to be transparent with the public. We need to set the gold standard when it comes to transparency and those who are not as open will soon look out of place.”

She noted that in 2020 the UK public donated £11.3bn to charities, and said “they deserve to know how that money is being spent”.

“The most important currency for charities is trust, and given the privileged position and authority they enjoy they have an even greater responsibility to be open. Transparency builds public trust in our sector and without it we cannot serve our communities.

“At NCVO we believe charities should publish the exact salary of their highest earners and this information should be no more than two clicks away from their home page.”

‘We strive to be fair and open’

A Cancer Research UK spokesperson said the decision to publish the exact salary of their highest earner was about “maintaining public trust” in its work, adding “we strive to be fair and open in what we say and do”.

They said: “That’s why we share the details of our CEO’s salary on our website and a detailed breakdown of staff pay in our annual report and accounts.”

The General Medical Council (GMC) also publishes the exact salary of their highest earner on their website.

A GMC spokesperson said as the independent regulator of doctors, it follows the principles of good governance set out in the Charity Governance Code, including acting with openness and accountability.

They said: “We want to be leaders in the way we follow these values and believe we should be able to clearly account for both our regulatory and operational decisions.”

The charity said it published annual salaries based on the Information Commissioner’s Office guidance and summarise the salaries of our highest paid staff; the reports are publicly available online “for clarity and ease of reference.”

Similarly, the RNLI said it “strives to be transparent” and as it is funded by the “generosity of our incredible supporters, we are fully accountable to them”, hence the decision to publish the exact salary on their website.

‘We owe it to our donors to be transparent’

Other charities going beyond reporting requirements included household names, such as National Trust and the British Heart Foundation.

Liz Girling, head of inclusion and belonging at the National Trust, said: “As an independent charity with significant public interest in our work, we feel it is important to be open and transparent about our finances, including senior pay. As such, we choose to share our director-general’s salary in full.”

Kerry Smith, chief people officer at the British Heart Foundation, said: “We owe it to our donors to be transparent about how we spend their money, and that this information is easily accessible. As part of this commitment, we choose to publish a clear explanation of our reward policy and pay details of our chief executive in both our annual report and on our website.”

A Sightsavers spokesperson told Civil Society News transparency in all areas, not just senior staff salaries, is very important.

They said: “We strongly believe we need to be accountable to our supporters, donors and partners if we are to maintain their trust and support.

“We aim to perform to the highest standards, and we aim to be as transparent as possible over how we operate, how we spend the money we raise, and how we perform as an organisation.

“Sightsavers commits to publishing a report each year in which we share our performance across a range of accountability standards. We use this process to reflect on our performance and ways of working so we can learn and improve. As well as publishing salaries on our website, we also publish our policies on things such as whistleblowing, and global expenses, and data on programme finances.”

Related Articles