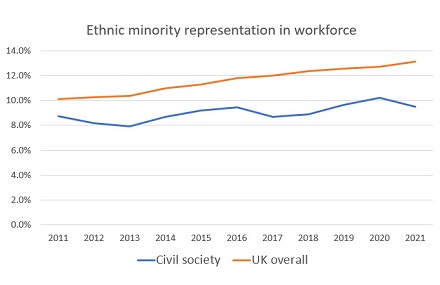

The proportion of workers in the charity sector from ethnic minority backgrounds has decreased, while representation in the wider UK economy has risen, figures from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) show.

DCMS’ estimates for January to December 2021 show that 9.5% of the civil society workforce were people of colour, compared to 13.1% for all UK sectors.

Civil society has consistently lagged behind the wider economy on ethnic minority representation over the past decade but the gap increased last year.

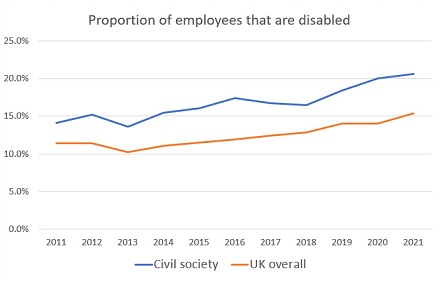

In contrast, a greater proportion of workers in the charity sector (20.6%) were disabled than in the wider economy (15.4%) in 2021, although the latter figure increased more from the previous year.

In civil society and the wider economy, filled jobs overall reduced from 2020 to 2021, but figures were up on 2019 for both sectors. In 2021, the civil society workforce was made up of 927,000 filled jobs, a decrease of 4,000 (0.5%) compared to the previous calendar year, but an increase of 30,000 (3.3%) since 2019 (pre-pandemic).

Racial diversity gap widening

DCMS’ figures, which are calculated using the Office for National Statistics' (ONS) Annual Population survey (APS), have consistently shown ethnic minority representation in the charity sector more than two percentage points lower than in the UK economy overall since 2012.

Moreover, the latest release published last month, shows that this gap widened to 3.6 percentage points in 2021.

The proportion of workers in the charity sector from an ethnic minority background decreased from 10.2% (94,000) to 9.5% (88,000) from 2020 to 2021, while representation in the wider economy increased from 12.7% to 13.1% year-on-year.

Nicole Sykes, director of policy and communications at Pro-Bono Economics, said that the impact of the coronavirus pandemic and a lack of access in the charity sector to people from lower income families were possible factors.

“We know that Black-led charities, particularly small ones, really struggled during Covid. We know that that was a factor,” she said.

“I think we also know that people from more privileged backgrounds are more likely to both get in and get on within civil society.

“So, we know that if you are from a more advantaged background, you are more likely to get a job in the first place, but then also rise up the ranks and get managerial jobs within civil society.”

The Living Wage Foundation recently published a report showing a decline in the proportion of low-paid workers in the charity sector.

But the foundation warned that low-paid workers were more likely to become unemployed during the pandemic, which could have skewed the figures.

Sykes said it was possible the increase in unemployment of low-paid workers could have particularly affected people from ethnic minority backgrounds.

“Surveys were suggesting that people, particularly in events, and fundraising roles, were the ones who were more likely to be losing their jobs during the pandemic,” she said.

“I don't think we have the data to say what those roles were being paid, or what the ethnic minority representation within those roles were. I think people like street fundraisers, for example, and door to door fundraisers are not paid a lot of money. And it's not surprising that these jobs are being lost. So yes, there could absolutely be a link in there.”

Disability representation gap narrows

In contrast, charities have consistently had a greater proportion of employees that are disabled than employers across the wider UK economy.

The proportion of jobs in the economy overall occupied by disabled people rose by 1.4 percentage points from 2020 to 2021, possibly due to the shift to remote working during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Representation of disabled workers in the charity sector also increased, but to a lesser degree (0.6 percentage points).

This still meant 5,000 more disabled people held civil society jobs in 2021 (from 186,000 to 191,000) despite there being 5,000 fewer filled jobs overall (from 932,000 to 927,000) than the year before.

Since 2011, the proportion of charity sector workers that are disabled has increased from 14.1% to 20.6%, while representation in the wider sector has risen from 11.4% to 15.4%.

Sykes said the figures were “good news” for the charity sector and that the rise of remote working during the pandemic may have helped disabled people enter the workforce.

“I think we already knew that civil society is a good employer of people with disabilities,” she said. “But also that maybe the pandemic with working from home etc helped play a role in getting more people into working life.”