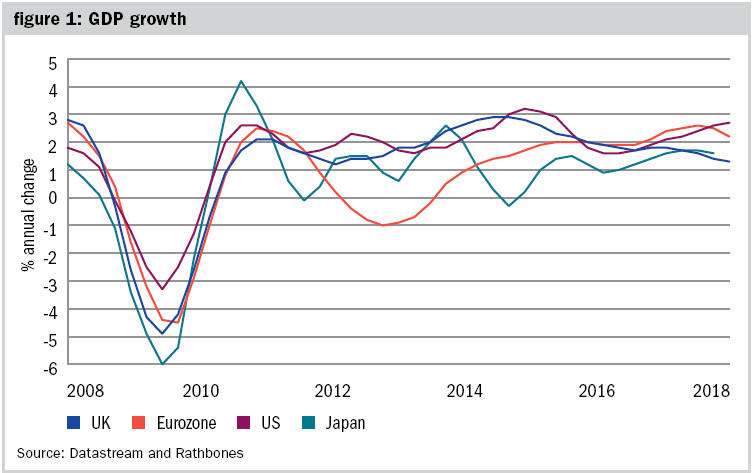

Throughout 2017, the global economy enjoyed a period of synchronised growth. However, the pace of the expansion slowed slightly in 2018 and momentum was more uneven around the world. Populist politics was a dominant theme and more risks emerged, including escalating trade tensions, diverging monetary policies and a strengthening US dollar.

In America, President Trump’s tax cuts helped lift the annualised quarterly growth rate above 4 per cent towards the end of the year, and unemployment fell to its lowest since 1969. The jobs market was strong, consumer spending was buoyant, and US companies continued to report strong earnings at home and abroad.

In particular, technology stocks and growth sectors outperformed with a select number of companies propelling the US stock market to record highs. Apple beat Amazon to become the world’s first trillion-dollar public company, surpassing the landmark valuation at the start of August.

Trade hostilities broke out between America and its allies after the Trump administration said it would set tariffs on a wide range of imports from around the world. Negotiations with China stalled and the two countries became locked in an ongoing trade war after the US imposed tariffs on $250bn of Chinese goods. China retaliated with its own tariffs on a similar proportion of American imports.

A long hot summer

Largely due to uncertainty surrounding Brexit, the UK economy got off to a slow start in 2018. GDP grew just 0.1 per cent over the first three months of the year and then by 0.4 per cent between April and June. The dominant service sector again led economic growth with engineers, accountants and lawyers all enjoying a busy period, backed by growth in construction, which hit a record high.

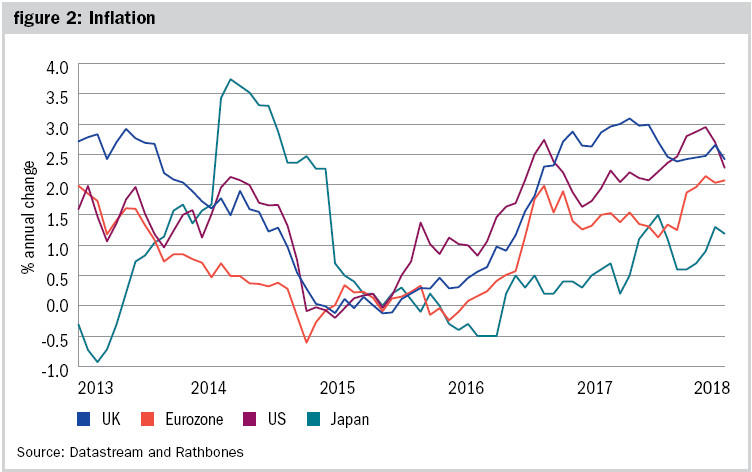

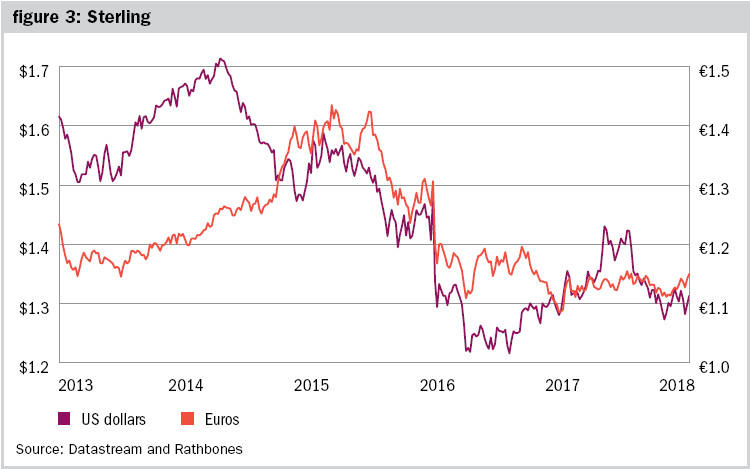

The sharp fall in the pound that followed the EU referendum in June 2016 prompted inflation to spike. Having peaked at over 3 per cent in November 2017, consumer price inflation hovered around 2.5 per cent for most of 2018. That was largely because the effects of the pound’s depreciation fell out of the figures. Meanwhile, wage growth outpaced inflation in a strong jobs market, where an unemployment level of 4 per cent is the lowest since 1975.

The tough environment for Britain’s bricks-and-mortar retailers claimed two more victims at the start of 2018, with Toys R Us and Maplin Electronics going into administration. The casual dining sector also struggled, while Marks & Spencer announced more store closures. In August, House of Fraser entered administration after 169 years in business, although many of its stores were spared closure through the insolvency process. One of the main reasons for these business failures is the rising popularity of online shopping.

Brexit negotiations with the European Union continued to dominate the UK’s political landscape throughout 2018. Among the many points of disagreement, the Northern Ireland border remained one of the most intractable challenges. The possibility of a longer period of transition following the March 2019 deadline appears to be the most likely outcome, which would allow the UK to retain some access to the EU’s markets.

Continental questions

At the start of 2018, the outlook for the EU’s economy was optimistic. Growth at the end of 2017 had been surprisingly strong, suggesting that the crisis years were receding nicely. However, GDP figures during 2018 have been disappointing. As a result of lacklustre activity throughout the region, the euro weakened against other major currencies, including the US dollar.

The deceleration was partly because demand for exports slowed. Even Germany took a knock. So too did the region’s second-largest manufacturer, Italy, where trade was not the only story. Investors became uneasy after its populist coalition between the anti-establishment Five Star Movement and right-wing League entered office in June.

Later in the year, Italy’s political turmoil unnerved markets further after it placed itself on a collision course with the European Commission by proposing a budget deficit that breaks the region’s rules. Since economic growth is anaemic, this would probably result in a further increase in Italy’s already huge debt stock as a proportion of GDP.

On a more positive note, the US and EU agreed to avoid an all-out trade war and work to lower tariffs. President Trump put aside his threat to impose tariffs on European cars, and the EU said it planned to buy more US liquefied natural gas and soybeans. However, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) nudged down its expectations for EU growth in the year ahead.

After months of hinting, the European Central Bank (ECB) confirmed plans to wind down its programme of quantitative easing by halving monthly bond purchases to €15bn from October. It later announced it would stop buying new bonds by the end of the year, and suggested that interest rates would remain unchanged through to the end of summer 2019.

Abenomics is working

It is now five years since Japan’s prime minister Shinzo Abe unveiled a comprehensive stimulus package to revive his country’s economy from two decades of stagnation. This programme became known as Abenomics, and comprises aggressive monetary easing, fiscal spending and structural reforms.

It appears to be working – the world’s third-largest economy has enjoyed one of its longest stretches of uninterrupted growth in the past two decades. Additionally, Japan’s stock market reached its highest level since the early 1990s at the beginning of 2018.

Although Mr Abe faced political challenges from within his own party, his reforms that make up the third arrow of Abenomics continued. There have been encouraging developments in attempts to reduce overtime, encourage more women into the workforce, boost immigration and improve wages.

Diverging from other central banks that have moved to unwind their stimulus programmes, the Bank of Japan said it is committed to keeping interest rates extremely low for the foreseeable future and pledged to continue buying bonds. Haruhiko Kuroda, the central bank’s governor, said the forward guidance should counter speculation that the bank is heading towards an early exit or an increase in rates.

However, many Japanese businesses caught in the crossfire of the trade war between America and China face a dilemma: change how their products are assembled or bide their time until the world’s two largest economies reach a compromise. Meanwhile, a stronger yen has been negative for exports.

Emerging markets begin to struggle

When interest rates rise in America but nowhere else, the dollar tends to strengthen. That makes it harder for emerging market governments and companies to repay their dollar debts. A rising dollar helped propel Argentina and Turkey into trouble in 2018.

Problems in Turkey were intensified by the threat of American sanctions in a row over the detention of an American pastor, which sent the lira reeling. Meanwhile, Argentina’s central bank more than doubled its benchmark interest rate to about 70 per cent – the highest in the world – after the peso fell to a record low against the dollar.

However, these instances appeared to be largely isolated. Government finances in Turkey and Argentina are much worse than most other emerging markets, which have improved significantly since the taper tantrum in 2013, when the Fed first announced it was tapering its bond-buying programme. Notably, Turkey has a large current account deficit and inadequate official reserves.

China’s economy slowed throughout 2018, growing by 6.7 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter, down from 6.8 per cent in the previous three quarters. That counted as a strong result against headwinds from trade tensions with America and the government’s efforts to rein in debt. However, GDP growth slowed further in the third quarter to an annualised rate of 6.5 per cent.

This was the slowest rate in a decade and hinted at vulnerabilities, including deleveraging in the shadow-banking sector and the impact of America’s tariffs. Although China is likely to beat its official growth target of 6.5 per cent for 2018, measures to boost confidence and the economy are likely over the year ahead as the government manages the transition away from traditional heavy industries and exports and towards services and domestic consumption.

Are we nearly there yet?

It’s been ten years since the defining moment of the global financial crisis — when Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy and employees piled out of its headquarters on Wall Street with their personal belongings. Following a swift response and extraordinary measures from policymakers, the US economy pulled out of recession in June 2009, and it hasn’t looked back since.

However, the recovery’s been going on for so long, that many investors are wondering if the end is nigh. This is now the second-longest period of growth in American history, having recently matched the expansion from 1961 to 1969, an era of big government spending under presidents John F Kennedy and then Lyndon B Johnson.

Unlike the rapid growth of the 1960s, the current expansion hasn’t been setting any records for its speed. It’s taken a long time for unemployment to get back to healthy levels and wages have only recently begun to accelerate ahead of the rate of inflation. The tortoise-like nature of the recovery may help account for its longevity.

The slow speed has prevented the US economy from overheating. Despite three hikes already this year, official interest rates remain at just 2 per cent to 2.25 per cent. Economic expansions don’t die of old age, and we believe a recession is unlikely any time soon. The recovery could persist beyond July 2019, when it would surpass the 1991 to 2001 expansion as the longest on record.

Yet risks remain including political uncertainty created by populist politics. Most advanced economies now have viable populist or nationalist parties, waiting to capitalise on the first sign of renewed economic distress. America has an unpredictable president, and Britain is close to leaving the EU, possibly in a chaotic fashion. The political climate across the rest of the EU is complicated. Mario Draghi’s term as ECB president is set to end in October 2019, and big vacancies are also coming up at the top of the European Commission and European Council.

Monetary policy is another threat. Central banks can kill off long-lived booms, and monetary policy has been shifting. The Fed has slowly been raising its benchmark interest rate since late 2015. The Bank of England followed suit in 2017 and is expected to continue to increase interest rates slowly over the next few years. The ECB will probably raise its benchmark rate in late 2019. If it raise rates too quickly, it could slow down the global economy more than expected.

The escalating trade wars present one of the biggest threats to the global economy. The IMF has already warned that the tariffs on imports threatened by president Trump and the US’s trading partners could lower the annual growth rate. It has also expressed concerns that the divergence between advanced and emerging economies has grown over the second half of 2018.

US dollar strength poses a headwind for companies and governments that have borrowed in dollars. Although it’s slowed slightly, China’s economy looks resilient, as do conditions in most other major emerging markets. Although recent turbulence in Turkey and Argentina appears to be isolated, investors may remain cautious about the risk of contagion to other countries.

One surprise might be a rise in the cost of oil and prices have crept up over the past year, from $50 a barrel. Politically generated disruptions to supply in Venezuela and Iran could strain the market even further. Strained diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia over the death of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul could also complicate matters.

History tells us that the unexpected happens frequently in financial markets, which is why it is important to build diversified portfolios and actively adjust the mix of assets to reflect the evolving investment environment. Although the economic background is still looking perky, it will be necessary to keep a close eye on both politics and leading economic indicators over the year ahead.

Andrew Pitt is head of charities at Rathbones

Charity Finance wishes to thank Rathbones for its support with this article