As part of a wider feature on street fundraising worldwide, Stephen Cotterill highlights the fundraising potential of Brazil, Russia, India and China.

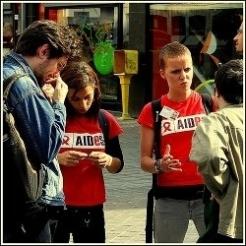

International face-to-face fundraising reaches the ripe old age of 20 this year. Through the care intensive early years of the late 1990s, the headstrong rebellious adolescence at the turn of the century to the established figure that it is today, face-to-face has been a game-changer for the sector.

The ageing process, however, can take its toll.

Markets have also matured and the public in some countries have grown tired of street fundraisers and are becoming stone-hearted to the causes they so eagerly promote. As result, in countries with saturated markets such as the UK and Australia income from this source is flatlining. Time for something new.

Innovation is one way; Amnesty’s virtual reality goggles, Unicef’s use of props such as life-size dolls spring to mind. The other is to seek out new markets.

On paper, the BRIC countries - namely Brazil, Russia, India and China - offer enormous potential for charity fundraising. Growth economies, burgeoning middle classes, improving infrastructure, increasing awareness of social responsibility – all the ingredients for a healthy donor base and steady unrestricted income surely.

Not so fast.

As well as opportunity, these jurisdictions present a peculiar set of challenges that have to be navigated. In India for example, traditional street face-to-face fundraising methods gain very little traction. Standing on a street corner and asking people for donations in Delhi or Mumbai simply does not get a response.

Instead, the charities that are proving the most successful in that space have adopted a hybrid form of telephone fundraising and face-to-face. Initial contact is made by phone to select individuals, such as small business owners, and an appointment is arranged where a face-to-face fundraiser will visit their home or workplace.

In Brazil, INGOs are currently facing major challenges with changes in the way credit card payments are being processed, as well as coping with a generally inefficient and unreliable banking system. In China and Russia, not only are their staffing and language barriers, but there are also political implications, particularly for those charities dealing with human rights and environmental issues.

Huge restrictions are placed on foreign NGOs in these countries, particularly when it comes to asking for money. WWF, for example, has upward of 300,000 signed-up supporters in China, but it cannot send them even a letter to ask if they want to give a donation.

It’s too early to say whether the BRICs will be the next boon for face-to-face, but for those charities that can tap into these emerging markets, the rewards can be great. SOS Children's Villages and Oxfam are making significant inroads in India. In terms of sheer volume, Brazil this year became Unicef's biggest single market for the acquisition of new regular donors, with an average donation of around £10 per month.

There are some promising signs on the horizon in other markets too. China, for example, held its first international fundraising congress earlier this year. A step in the right direction perhaps... the only problem being that international fundraisers are not actually allowed to ask anyone for money in the country.

This is an extract from a feature on street and face-to-face fundraising in October's edition of Fundraising Magazine, which will be published tomorrow. Click here to subscribe.