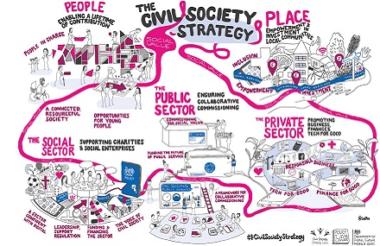

The government’s Civil Society Strategy, published last week, contained a lot of fine words about the voluntary sector. It identified, correctly, the main things the government needed to do to make its relationship with the sector useful. It is a very good document, aspirational and thoughtful and in tune with the sector.

There were two main threads. One was about working with the sector – giving charities a proper voice, and listening to what they have to say, without trying to silence them when they got too loud for comfort. This is important, and there were many kind words which provide encouragement, although no firm commitments.

The second key theme was about funding, which is what charities really turned up to hear about. Here there were good ideas, and plenty of them: more grants, more emphasis on social value in commissioning, more power to local people to commission services.

It is in truth, less of a strategy and more of a vision. The vision belongs to Danny Kruger, a former charity chief executive and Conservative speechwriter, who has captured perfectly an approach to the sector which makes sense for government. It is no doubt endorsed by Tracey Crouch, too.

But the document demonstrates a number of limitations.

There is no money

Notable by its absence, is the mention of any actual money. There was £21m of new funding in the document, to the best of my knowledge, of which £750,000 will come from government and the rest from dormant charities.

Meanwhile, the government is sitting on not one but two massive sources of funding – dormant bank accounts and dormant assets. Between them these constitute a £2bn endowment plus several hundred million pounds a year of income, which are supposed to be used to provide a significant pot of funding to community foundations, and thereafter to charities in those communities who need support.

Very little progress is being made on getting this done. Earlier this summer four industry champions were appointed to look at the issue and they will report to the minister by the end of the year, but it is unclear what will happen next.

It needs buy-in

The opaque nature of Whitehall means we can’t be sure why the dormant assets funding stream is taking so long to be realised. But the delays illustrate, once again, that even when the OCS is in tune with the sector, it is limited in its ability to actually deliver change on charities' behalf.

The OCS will also struggle to deliver against many of the other objectives in the document – renewing the Compact, a move back to grants, embedding social value. The siloed nature of government, and the lack of funding for the OCS, mean it isn’t possible for the people who outlined the vision to actually implement it.

Arguably this has always been the case. Even at the high point of the OCS, back when it was the Office for the Third Sector and was still in the Cabinet Office rather than its current berth at DCMS. Even when it had a budget seven times what it has now, it was never able to influence the people who mattered – those who actually provided funding. But it is certainly even less likely to have any influence while it is wedged in the dismal hinterland of the Ministry of Fun.

Possibly there is a strategy – just not one which is written down in this document. Possibly that strategy is to influence communities secretary James Brokenshire, and his key civil servants, to produce some rules telling local government to read this document and make it happen.

Because it is Brokenshire and his department (as much as anyone) who can influence whether local authorities actually return to grant funding charities, and whether they actually pay any attention to the Social Value Act.

Time for a new home?

This document illustrates the broader truth that if we want to make progress on the issues that exercise the sector (those to do with infrastructure, at least) then the charities brief might most usefully sit in the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government. That’s the department which influences how local councils spend the £60bn discretionary funding they have at their disposal – almost an eighth of which is spent with the sector, unless I read it wrong.

It’s also the department responsible for strengthening communities, and this is something that charities are absolutely central to. It’s the foremost purpose of most of the sector. If the government is genuinely interested in communities, it has to put charities at the heart of its strategy.

It’s not a perfect fit. While MHCLG is suitable for the small community organisations which make up most of the sector, and for the mid-sized charities which deliver local services, it’s nowhere near as good for big household name charities, or for social enterprise, which are very different beasts.

For the sector as a whole – though not for the household name bodies which rely on fundraising – the biggest challenge at present is the relationship with local government, and how statutory funding is delivered.

This strategy proposes many ideas for addressing that, but none of the mechanisms to enforce them. For that, what we need is a much closer dialogue with MHCLG and the representatives of the local authority sector. The question is how we deliver it.