Gemma Woodward assesses the positive attributes of infrastructure investments for charities.

Charities have been faced with one particular challenge over the last few years – how to generate a sustainable and growing income for charities from their investments. We all are well aware of the backdrop: low interest rates (with rumours circulating that banks have plans to charge non-personal customers to hold cash deposits with them) and the bond market continuing to defy conventional mathematics. The result has been that investors looking for income have potentially been forced to take more risk by holding a higher weighting in equities in order to obtain that income stream.

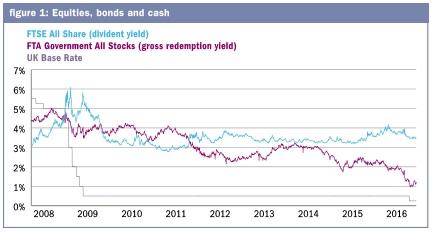

Below are the income streams from UK equities, UK government bonds and cash since 1 January 2008 to 30 September 2016:

Therefore charity investors have been looking for other sources of income, while looking to balance their risk profile at the same time. It goes without saying we would all love a 5 per cent return with very little expectation of losing capital (remember pre-2008 with interest rates at 5 per cent, albeit your real return, less inflation, would be half that).

However, we believe (based on our estimated forecast returns: see below) that to achieve an inflation (CPI) plus 3.5 per cent one has to move further into the equity and alternatives realms than in the past. Put simply, bonds and cash do not produce a return that will ensure a charity’s investments will keep pace with inflation, and more. The official UK rate of inflation (CPI) has started an upward trajectory, and is likely to increase further given the fall in the value of sterling, causing imported goods to cost more.

Transparent alternatives

Within the alternatives space, we favour for charity investors those which have transparency and produce an income: we do not invest in hedge funds within this area. One area we particularly favour – although the purchase price is critical – is infrastructure funds.

Infrastructure funds

The development of liquid and easily accessible infrastructure funds over the last decade has enabled new investors to participate in this asset class. The first infrastructure investment company was listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2006. Given the illiquid nature of infrastructure, the permanent capital structure of investment trusts is suited to this type of investment, with supply and demand dictating whether the vehicle trades at a discount or a premium to its net asset value.

The attraction of infrastructure funds (be they for the building of hospitals, courts or related to renewable energy projects) is that they offer a level of income which is at a significant premium to that of the gross redemption yield of a UK ten-year government bond; yet the projects have government backing and usually inflation-linked returns. Therefore from an income perspective this provides both certainty and sustainability, with growth prospects. This certainty and sustainability of the income stream is of paramount importance.

Many charities commit to providing funding for projects over a fixed timeframe and in many cases meet this funding from their investment income. If the investment income is insufficient then there is a funding gap which ultimately affects the charity’s ability to deliver its objects.

Obviously if the charity is able to expend capital, it may then drawdown funds from its portfolio, or it may be able to fund from other sources. However, in some cases, if the charity is a permanent endowment it is limited to spending only its income.

For charities, there is a further attraction to investing in infrastructure as it has many positive social attributes. In many cases, charities will avoid investing in certain sectors or activities as they are not in keeping with the charity’s objectives or will create reputational risk issues. As we have seen in the past, a charity investing in an area which is deemed inappropriate is manna for parts of the media.

Charities have been at the vanguard of ethical investing and certainly much of the focus has been on exclusionary policies, however for many charities the focus has widened from excluding investments on ethical grounds, to also seeking investments which have a positive impact on society. Obviously this does not always make a perfect match, for example a faith-based charity may not wish to invest in GP surgeries which provide abortifacients to patients, despite the other positive attributes of such an investment.

It is unlikely that positive factors will ever be so significant that they will mitigate negative issues as the latter are integral to a charity’s ethos, and this, of course, needs to be taken into account when selecting any investment, not just infrastructure funds.

Tangible benefits

For us, as investors, there is an inherent pleasure in including investments which not only deliver the investment requirements set by charities, but which also provide other tangible benefits – it is a feel-good story which goes beyond rhetoric and delivers societal impact.

Obviously this is one factor which has to be assessed alongside others. For example, the income is attractive in this time of low interest rates and bond yields, however, one must always be mindful that the income in some instances is a very significant proportion of the total return, and as for many charities preserving the real value of the capital of the portfolio is equally an important consideration, this must be taken into account.

Likewise consideration must be given to the overall investment case for the specific infrastructure fund. Sometimes the case for taking ESG (environmental, social and governance) or responsible investment factors into account seems to be lost in the wider investment context.

I was at a presentation recently where the focus was on how an index had been divided into the top 50 per cent ESG performers and the bottom half. The performance of these two groups was then plotted and the top 50 per cent ESG cohort had outperformed the other.

However, the performance differential was not significant and more than one cynic in the audience noted that it did not make a powerful case for including ESG factors in your investment decisionmaking. The point, of course, that we never judge an investment on one criterion, there are always multiple factors in assessing its efficacy. However, infrastructure with its income generating qualities and its positive societal impact, meets the requirements of many charity clients.

Gemma Woodward is director of responsible investment at Quilter Cheviot

Civil Society Media wishes to thank Quilter Cheviot for its support with this article