In his 1985 polemic The Past is a Foreign Country, the charismatic cultural historian David Lowenthal analysed how each generation seeks to reshape its legacy by selective suppression of some aspects and celebration of others. As we commemorate the end of the Great War, this observation seems no less true in the current environment.

Our collective consciousness seems imbued by the mud and blood of Flanders, the slaughter and sacrifice of a generation now fading in memories. Few in the media seem interested in celebrating the crowning achievements of Field Marshal Haig and the four victorious Allied Armies during the hundred days offensive of quick-fire battle successes that began in August 1918 and ended with the Germans suing for peace in November. Even at the time, the chief of the imperial general staff, Sir Henry Wilson, was gloomily advising the War Cabinet to prepare for another year of fighting while Winston Churchill, as minister of munitions, was writing to Haig asking him to conserve his forces for 1920.

Haig saw otherwise as all his stars suddenly became aligned. He seized the opportunity and in a stunning series of bounds that vindicated all those previous wearing out campaigns, he oversaw the series of successful battles that sent the Germans reeling and finally brought about peace.

As Lowenthal went on to write: “History can be hard to digest. But it must be swallowed whole to undeceive the present and edify the future.”

As one surveys the current geo-political landscape and leaders who people it, one could be forgiven for thinking that few of the latter have looked to history to help guide them as to their options for the future. In October 2018, US vice-president Mike Pence laid out in stark terms America’s intention to confront a rising China across the board: over its interference in American politics, its trade policies, its theft of intellectual property and plans for industrial development, cyber-attacks, security, debt diplomacy and culture of censorship. In other words, he was reiterating President Trump’s core policy of putting America first. To many, this seems strongly like the beginnings of a new cold war, if not an increasingly hot peace.

As trade war rhetoric between today’s two great economic superpowers escalates, it is instructive to turn to history and look to see where previous periods of protectionism were the precursors to armed conflicts.

One interesting parallel is the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. Republicans Reed Smoot and Willis Hawley advanced this legislation with the intention of gaining greater control over the flow of trade, thereby supporting US industries, safeguarding American workers and boosting the economy. President Hoover was initially sceptical of the plan and refused to endorse this act. Eventually, however, he succumbed to political pressure and let it through.

It is a cruel irony that the proposed beneficiaries of such protectionism are invariably those who suffer the most. The Smoot-Hawley Act led to the significant deterioration of US trade and exacerbated the recession that consequently became the Great Depression. Between 1929 and 1933, US GDP tumbled 30 per cent and US exports dropped from $5.2bn to $1.7bn. This resulted in mass unemployment and crushing levels of poverty. By 1933, 60 per cent of Americans were classified as poor, and between 30 and 40 per cent of banks collapsed.

Debt and greed helped cause the stock market crash of 1929. The Smoot-Hawley Act, however, magnified and prolonged what became the Great Depression substantially. For investors, it was catastrophic, with stocks plummeting 90 per cent from peak to trough (1929-1932). This was in the context of the Dow Jones having increased 300 per cent from 1924 to 1929.

Although a very different situation, President Trump’s easy-to-win trade war needs to be viewed with some circumspection. Whereas the Cold War between the West and the former Soviet Union was limited to ideology and defence, the damage a US-China conflict could do to the global economy and prosperity could potentially be huge because the two countries have become so interdependent. Furthermore, the flashpoints of strategic rivalry – North Korea, Taiwan or the South China Sea – could become the next Cuban missile crisis.

“We will not relent until our relationship with China is grounded in fairness, reciprocity and respect for sovereignty,” said Pence, without specifying who and how this state of affairs was going to be adjudicated. China understandably fears that the US wishes to halt its rise.

The Great War may have been inevitable but no one thinks it was a good idea. “The US has good reason to avoid the open-ended conflict Pence declared,” wrote Martin Wolf in the Financial Times recently. China is not an ideological rival and any conflict would be costly. The US also recognises that China has huge assets, not least its sizable – and growing – population, its dynamic economy and its significance as a market for many other countries.

In order to avoid conflict, the US and everybody else need to recognise that China is different and unlikely to conform to Western ideals of democracy and behaviour; if anything, we are increasingly likely to become more like China. Any attempt to halt China’s growth and development is plainly wrong. Far better to recognise that she is a vital and essential trading partner. Managing the stability of the world economy and tackling such issues as climate change will not be possible without co-operation with China.

“It is on the creation of new ideas that we depend, not the protection of old ones,” continued Wolf. “That in turn depends on freedom of inquiry and openness to the best talent from around the world….Our enemy is not China.”

As we commemorate the end of one great conflict that overshadowed the world for the rest of that century, let us not forget the lessons that history has to teach. As far as investment strategy goes, real capital preservation remains a high priority. We remain cautious in our overall approach and asset allocations. Within our core, low-risk and low-volatility capital preservation strategy allocations to cash and near cash stand at an all-time high of nearly 60 per cent, with fund managers keeping a wary eye on the course and direction of interest rates.

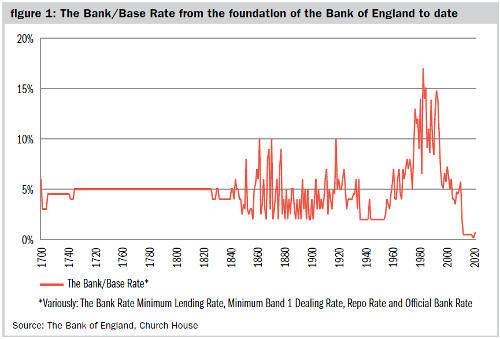

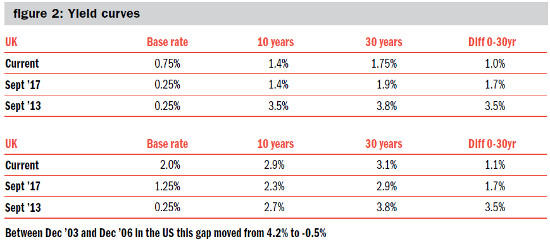

There is a strong sense of having reached an important inflexion point in fixed income markets as central bankers everywhere strive to normalise the floor at which capital is lent to corporates, individuals and governments. With the cost of capital set to rise, the norms of the past ten years look set to become another part of history soon.

Maintaining a long-term view and a balanced appetite for risk is, as ever, of crucial importance to ensure the peace of mind that charities value in these ever uncertain times.

James Johnsen is a director at Church House

Charity Finance wishes to thank Church House for its support with this article